Engraving Glass to Expose Oceans in Peril

If an elderly Bohemian master glass engraver and political dissident with a passion for poetry offered to help you explore the secrets of the universe, what would you say? “Yes,” obviously.

At least, you would if you’re April Surgent, a renowned glass and multimedia artist, whose work explores ocean ecology and climate change. In 2003, she enrolled in master craftsman Jiří Harcuba’s glass engraving workshop at Pilchuk Glass School. Determined to save glass engraving from obscurity, Harcuba taught contemporary approaches to the craft, encouraging his students to listen to the world and its “secrets.”

“The first thing he taught was that engraving is easy and that anybody can do it,” Surgent tells me. Perhaps sensing my doubt that I could coax photorealistic images out of a notoriously breakable material, she explains that while Harcuba taught technique, his focus was accessibility and liberation. “The first thing he teaches in his class is just to go for it and explore and not be bound up by the historical limitations of the craft. He was really pivotal in empowering me to just explore.”

Before she met Harcuba, Surgent was studying glass blowing, a diversion that “saved” her as a teenager. “I wasn’t really in a lot of trouble, but I was on that trajectory,” she says. “I found glass, and it was something that I fell head over heels in love with.” Studying at the Australian National University, however, Surgent found that making cups and bowls left her uninspired. She considered dropping out of glass, until, in her third year of study, she got a scholarship to Pilchuk Glass School and switched her focus to engraving.

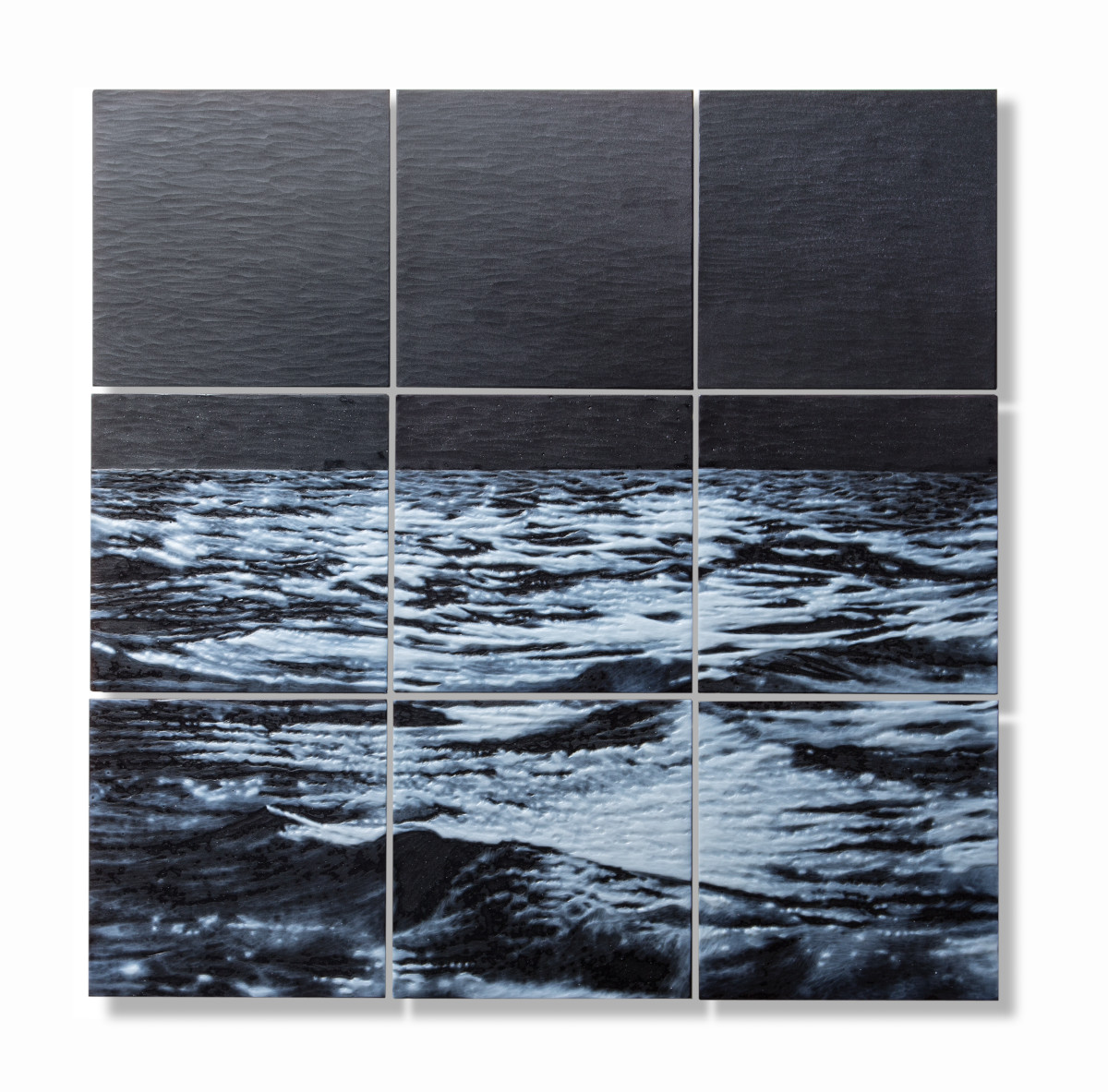

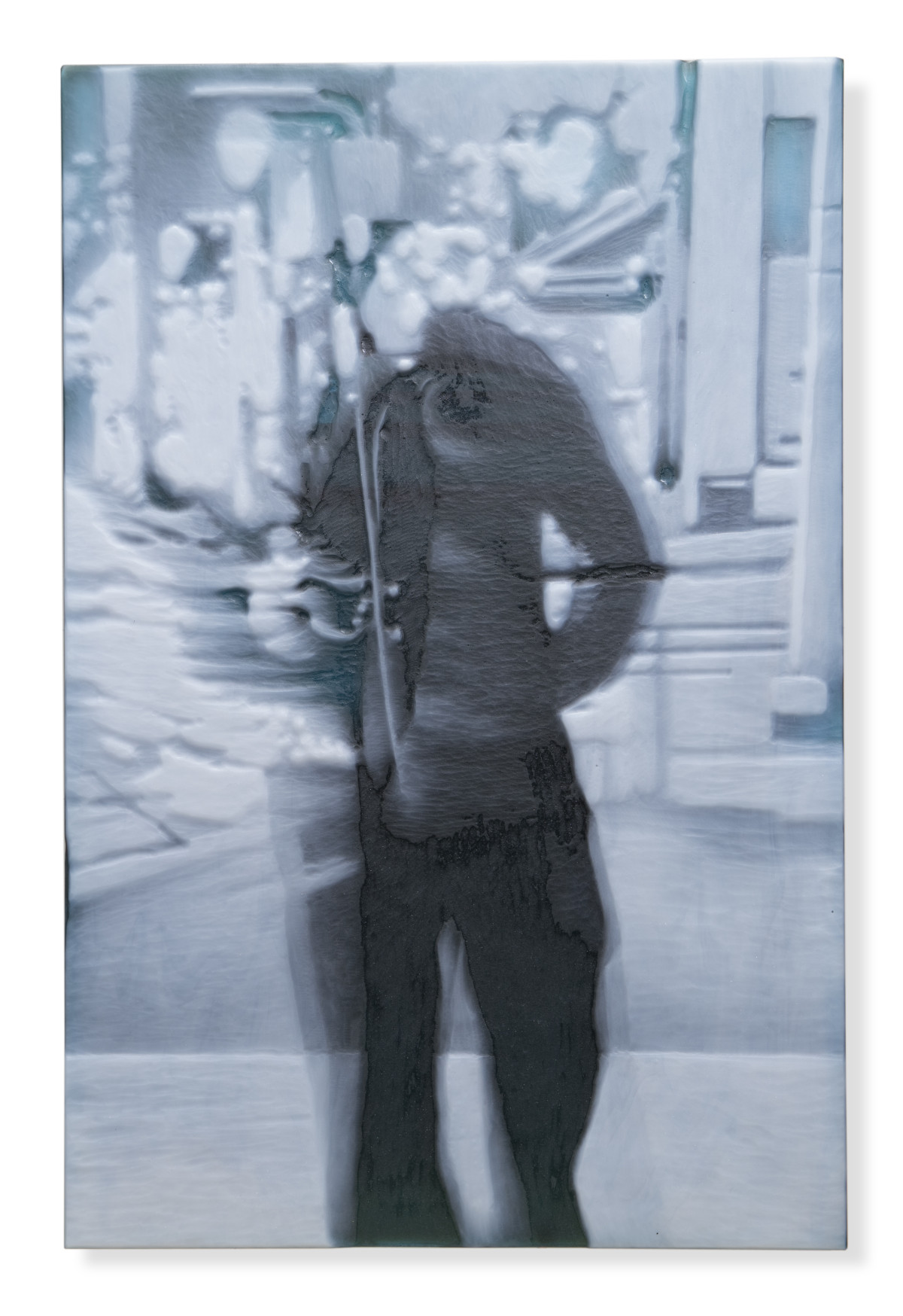

To make one of her cameo engravings, an engraving where an underlying layer of material is exposed as a background for a low-relief design, Surgent emphasizes the importance of good materials. “Glass has an annoying way of breaking a lot,” she says, smiling. She buys hand-rolled sheets of coloured glass from Bullseye Glass Co., cuts them down to small panes, and melts them together in a kiln. “I’m melting them together kind of like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich,” she explains.

Having already worked out her composition on paper or her computer, Surgent takes the glass to her engraving lathe. Using the rapidly rotating wheel, like a metal smith’s grinder, and using water to keep dust down and the glass cool, she carves her designs. “It’s a lot like drawing but like taking the paper to the pencil,” she tells me. A small panel can take her a week, and a larger piece with multiple panels can take a couple of months.

Picturing glass shattering and shards flying, I ask if the work can be dangerous. Surgent shakes her head, assuring me that “it’s a pretty benign process.” The biggest danger is inhaling glass particles, so Surgent wears a HEPA respirator, eye protection, and ear protection (it can get loud). She says, “Everything is very calm. It fits my low energy vibe pretty well.”

This calm also helps prevent mistakes. “It’s a really slow process, so to remove too much material takes some effort and some time,” Surgent explains. “More often than not, if I have to remake a piece, it’s because there’s been a crack, or it’s broken.”

Going slow and steady is part of Surgent’s life philosophy. In a time when technology is developing faster than ever and demanding we keep pace, Surgent tells me that working with her hands in a meticulous, measured way helps her disconnect from the tizzy. She feels that the way we live our lives has changed immensely in the recent decades, saying, “I feel like we can learn so much from history, and I feel like the engraving, in a way, keeps me connected to history in a more abstract way.”

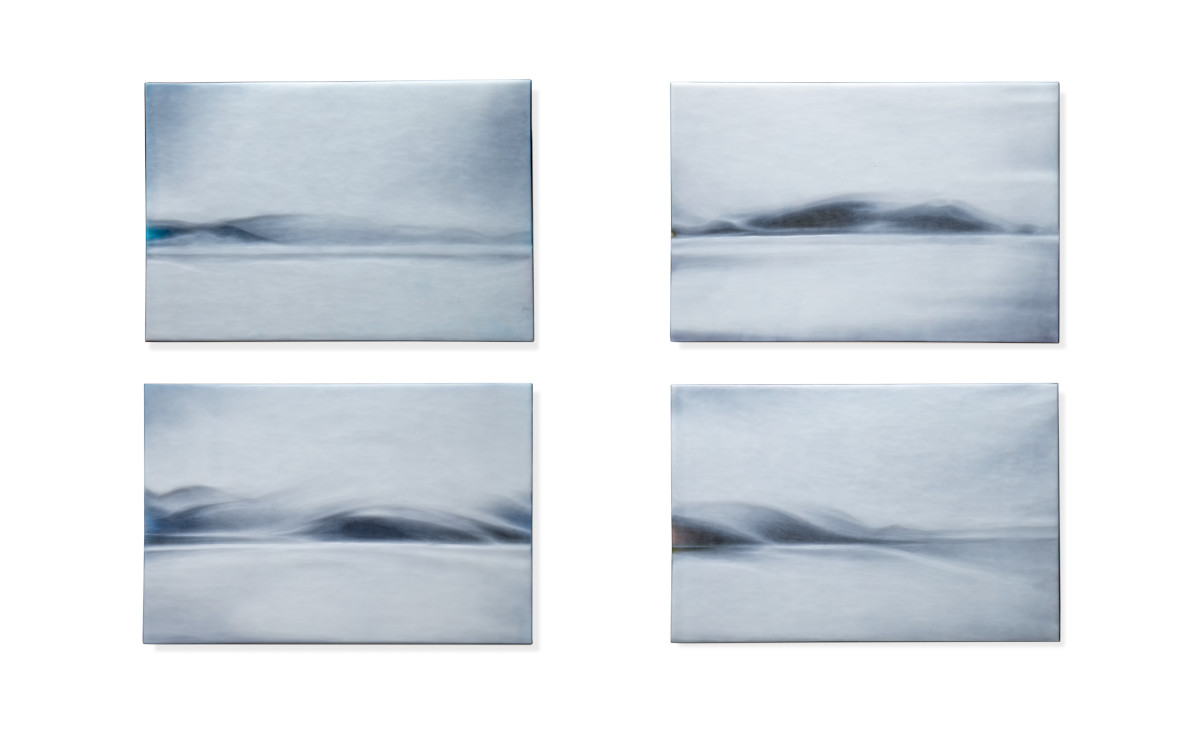

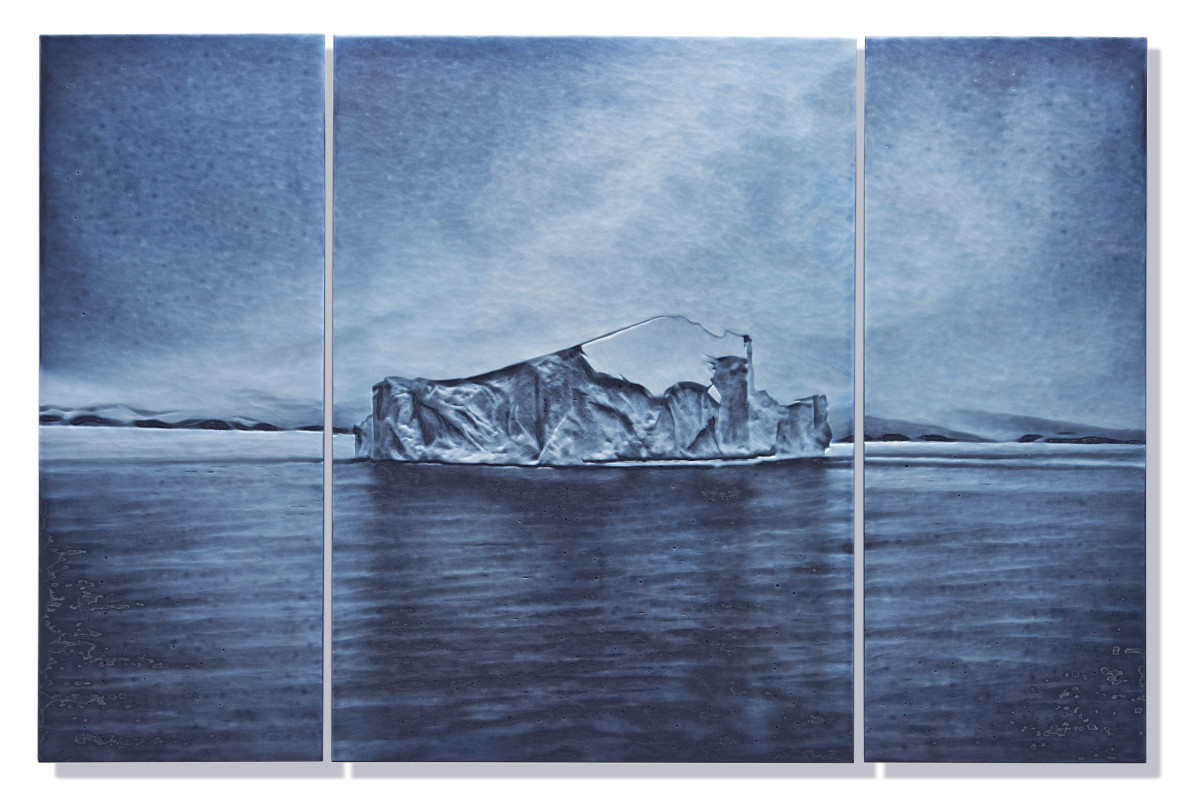

Another connection for which Surgent advocates is that between art and science, which was made tangible for her in 2013, when she travelled to Antarctica with the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. Surgent tells me that “it was the first time that I’d really seen research science in action, and it just kind of blew my mind how similar what I was doing…was to what the scientists were doing. And obviously they were doing it very meticulously in a very professional and methodical way, but ultimately, I felt we were looking for the same things through very different lenses. Not necessarily that I was trying to figure out what southern giant petrels had for lunch or that type of thing, but the secrets of the world basically.”

An understanding of the world has never been more imperative. The devastating effects of climate change are something that Surgent explores in her work in the hopes of connecting the public to what can be an abstract, distant concept. After seeing the diminished glaciers in Antarctica, Surgent worked with research teams in the Hawaiian Islands in 2016, the Farallon Islands, California, in 2017/18, and Lower Cook Inlet, Alaska, in 2018 to learn more about ocean ecology and the impact of climate change. She emphasizes that her work is not a translation of science but is informed by the research. Surgent takes her observations home in the form of notes, pictures, and videos.

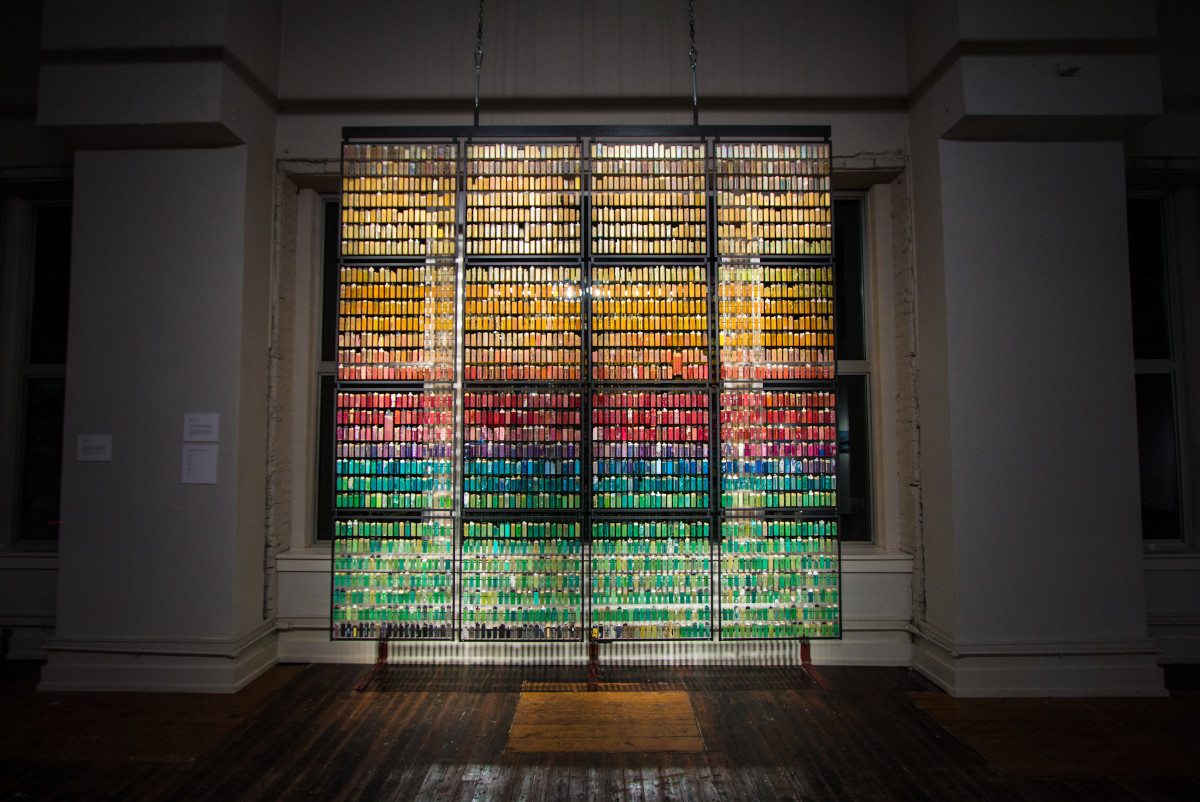

Or, sometimes, a boxful of garbage. Stationed at Pearl and Hermes Atoll, 1,200 miles from Honolulu, Surgent was shocked that the island was covered in “an insane amount of debris.” Seeing familiar objects like a tennis ball, a toothbrush, and a shoe, Surgent reflected, “Everything was something that I personally used, and it was this kind of like, ‘holy cow, maybe it does matter what I do.’” With the help of the research biologists, Surgent collected hundreds of disposable lighters that, back home, she assembled into her arresting piece Portrait of an Ocean. Biologists continued to mail her lighters from the surrounding atolls, and the installation grew from nine-by-nine feet to ten-by-eighteen feet. While the deliveries had to stop in 2020, Surgent hopes they’ll start again soon.

One of her more recent pieces, The necessity of establishing another way of life, reflects what its name suggests—the way we’re living is not sustainable, and we need to change. Informed directly by COVID-19’s bringing the world to a halt, the piece postulates that widespread behavioural change is feasible. “I think that humans are incredibly adaptable, and that change is possible,” Surgent says.

In that vein, she emphasizes that she doesn’t want her work to be all “doom and gloom.” “I’m actually making [some pieces] now that just embody what it feels like to be in nature, big open spaces, and hopefully start to build connections and relationships,” she tells me. “I think it’s incredibly difficult for people to feel connected to or care for things that they don’t inherently understand or that they’re not already connected to.”

Surgent’s work will be featured in an exhibition at the Traver Gallery in September 2021. You can also find her on her website and Instagram.

*

Featured image: The Last Frozen Ocean (2015) by April Surgent, 18.375 x 27.5 x 0.75 inches, cameo engraved glass

All images courtesy of the artist.

Share this Post