Devasher’s new film installation brings us closer to our closest star

In terms of familiarity, it’s hard to beat the sun. When your claims to fame include enabling the existence of life as we know it and also being really, really bright, you can’t go unnoticed. But how exactly do we understand this blazing ball of gas? We can’t even look at it, and we certainly can’t get close to it. Or can we?

One Hundred Thousand Suns is a film installation by artist and amateur astronomer Rohini Devasher. Created using over 100 years of data about the sun, the work celebrates the wonder and complexity of one of the most familiar objects in the sky and the practice of data collection.

The installation is comprised of four digital channels, or paradigms, each of which explores different ways the sun has been observed and recorded. They’re played simultaneously on four large screens, each with accompanying audio elements. The result is a dazzlingly multifaceted rendering of the sun that invites new perspectives and personal connections.

The installation opened this month and is accessible by appointment at the Open Data Institute (ODI) in London, England, until December 2022.

As Artist in Residence at the ODI, Devasher worked closely with the team at Data as Culture, the ODI’s arts program, who commissioned the work. The project had Devasher sifting through immense amounts of data—her personal observations from solar eclipses, her interviews with eclipse chasers, solar data sets from NASA, and roughly 120 years’ worth of data collected at the Kodaikanal Solar Observatory in India.

Creating the films themselves took about six and a half months but, Devasher says, sorting through all the data took at least two years. “To be honest, I was struggling with this material,” Devasher tells me. “There’s so much of it! I wasn’t sure how to pull it all together.” She chatted with the ODI’s team about digital twinning—using data about something that exists in the physical world to create a digital representation, or twin. The idea is that the digital twin will behave the same way as its real-world counterpart.

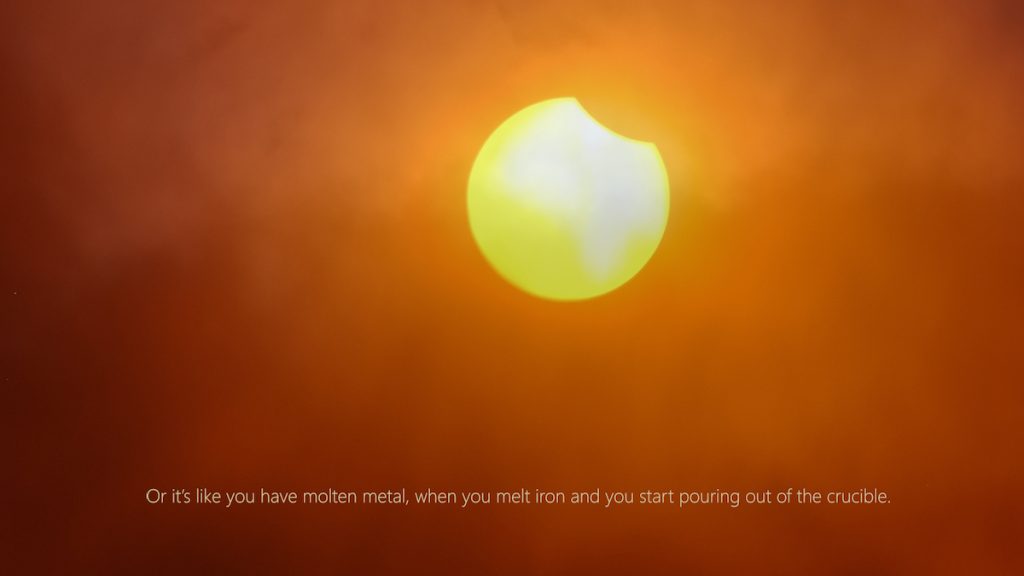

Devasher decided to probe that concept. “There are now people who are claiming to have created digital twins of the Earth, which blows my mind for all kinds of reasons,” Devasher says. “Because it suggests that the earth is knowable, and modellable.” Wanting to explore the distance between truth and a model, Devasher set out to create what she calls analogue twins of the sun, but with the critical nuance that “they’re speculative, they’re metaphoric. And they’re deliberately discreet. They’re deliberately messy.”

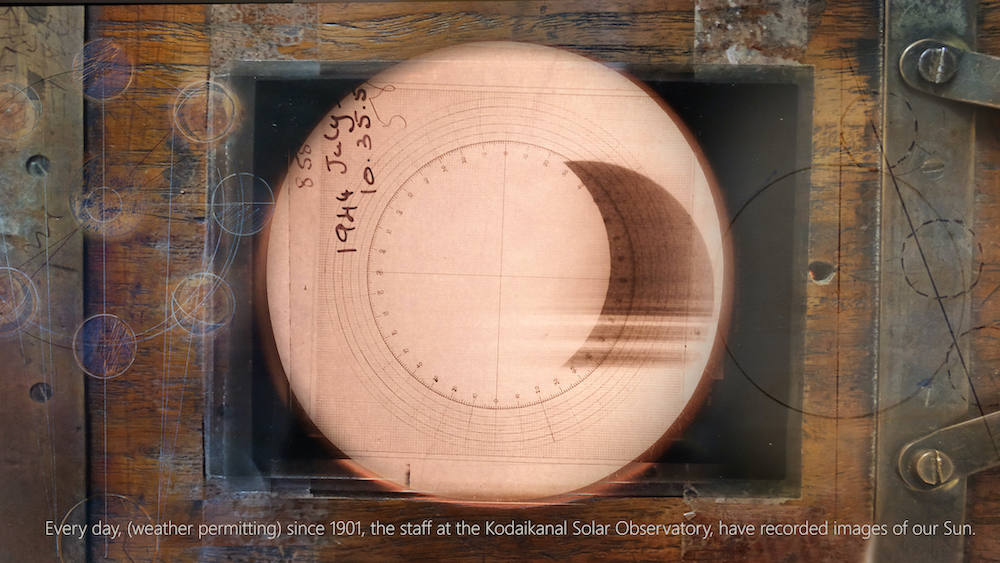

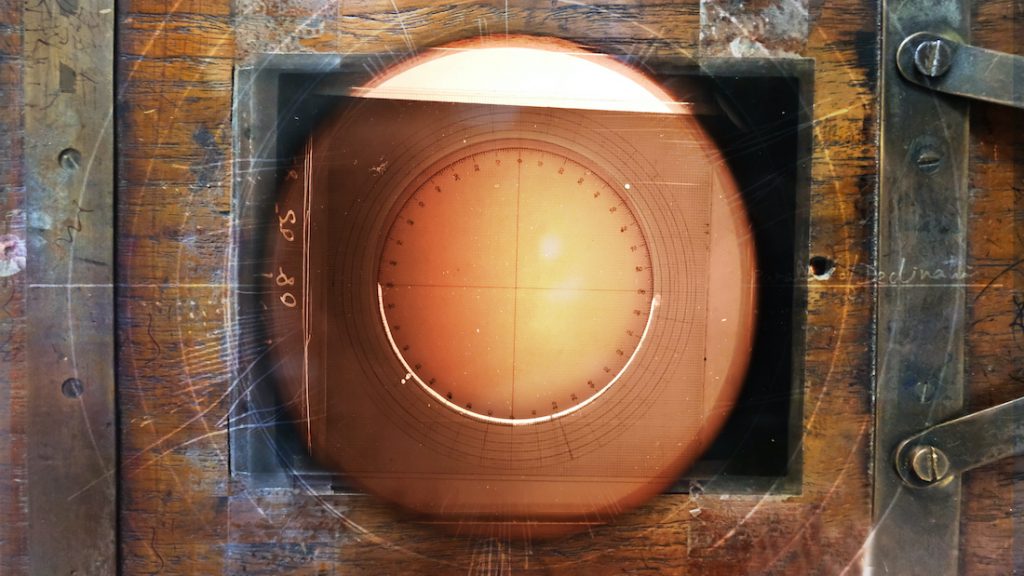

One Hundred Thousand Suns invites us to do the impossible and take a good long look at the sun, in many different ways. “Paradigm 1 Sun Drawings” showcases some naked-eye observations of the sun’s surface, drawn by hand between 1902 and 1904 at the Kodaikanal Solar Observatory. It’s worth noting that this observatory has collected over 157,000 images of the sun and its effects. They include these drawings as well as 19th century glass photographic plates, showcased in “Paradigm 2 Twin Suns.” Devasher adds drawings from her own sun data, done on carbon paper layered over a copper sheet (copper is forged in supergiant stars and discharged when they explode as supernovae). The flow of still images in these paradigms creates slow stop-motions of the sun over time.

By shaking up our perspective on something we encounter every day, by showcasing it in its brilliant complexity, Devasher cultivates something rare—a sense of wonder. “I feel like the word ‘wonder’ is losing currency more and more, not just in art, but in life in general,” she tells me. “And I just think it’s something that one has to make a case for more and more. Because wonder does walk this line between the strange and the uncanny.”

And indeed, elements of the paradigms are unsettling. In the second paradigm, an eye’s pupil opens impossibly wide until it resembles a solar eclipse. Unnerving atmospheric chimes and tones sound over the footage, as does a distinct heartbeat in the first paradigm (meant to represent the “solar heartbeat,” or reversal of the sun’s magnetic poles every 11 years). The data becomes imbued with a sense of instability and life.

The Kodaikanal Solar Observatory itself is featured prominently in “Paradigm 3 Site”—an amateur astronomer and friend of Devasher’s leads her around the facility and discusses its history. It’s impressive enough that the facility boasts over 120 years of continuous sun data collection. But even more impressive perhaps is that some of the people collecting it are the fourth generation to do so. “It was important also to sort of ground the site in the history of people who know it, who love it,” Devasher says.

As a whole, One Hundred Thousand Suns is rooted in passion. A sci-fi enthusiast from a young age, Devasher stumbled into astronomy when she was seeking out a science fiction club at university. Instead, she found the Amateur Astronomers Association of Delhi, who met weekly at the Nehru Planetarium. Devasher was drawn to the group’s dedication and diversity—people of all ages and backgrounds coming together to study the sky. Even in the summer. “I’m talking heat,” Devasher laughs. “We would meet at two in the afternoon every Sunday.”

It was with a group of amateur astronomers that Devasher chased her first solar eclipse, in July of 2009. She says the “absolutely incredible” experience gave her an unprecedented perspective of her physical relationship with outer space. “You’re suddenly aware that you are on a body in space. In between this conjunction of another two bodies in space,” Devasher tells me. “And, of course, there was screaming and shouting, because there’s no middle ground during an eclipse. People either go completely silent or there’s complete euphoria.”

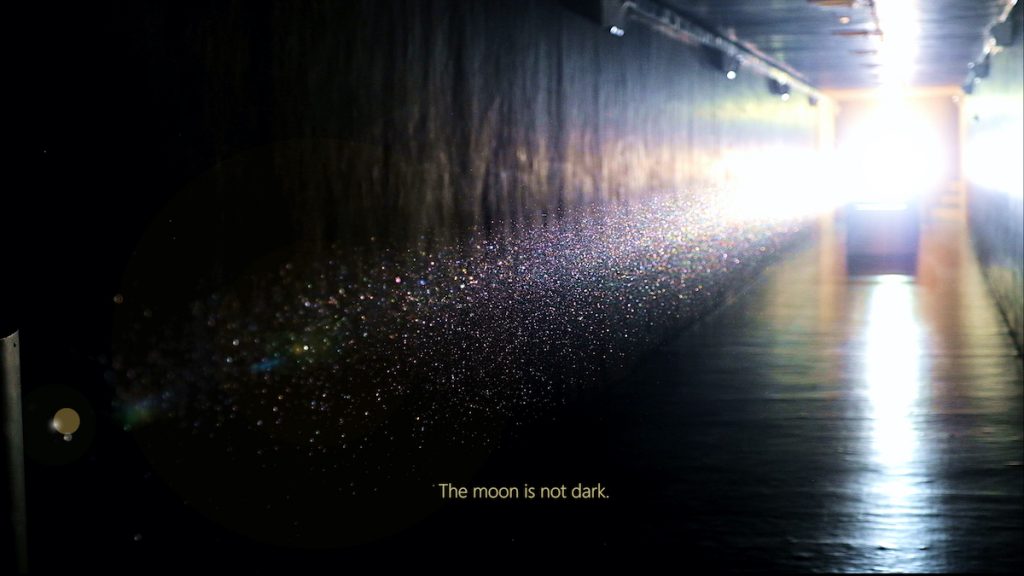

We hear excerpts from Devasher’s interviews with eclipse chasers (people who travel around the world to observe solar eclipses, sometimes planning years in advance) in “Paradigm 4 Eclipse.” One of them was a close friend of Devasher’s, who passed away due to COVID-19. “He talks about how he feels that he can read himself in the black of the moon,” Devasher explains. “He talks about how he doesn’t think you can even articulate that black. It’s a black shining, he says.”

In creating a data conglomerate, can we get at some objective truth about the sun? Surely, we can claim we know it, in an empirical way. After all, isn’t the point of data to be neutral, detached from the personal?

Not so, says Devasher. Whether we like it or not, there can be multiple readings of data. The process of data collection is inherently human, as is data itself, and it’s therefore not free of the messiness and biases to which humans are relentlessly prone. Devasher tells me how Dr. Julie Freeman, ODI art associate, spoke to her about data being “playful and malleable.” And, using the most poetic language about data collection I’ve ever heard, the ODI’s Head of Research and Development Olivier Thereaux told Devasher that “data is how we observe the things we love.” Devasher says this framework solidified what she had gleaned from the collaborative nature of the amateur astronomy world; she says, “People are important. People are central to data.”

Devasher tells me that a key takeaway from her residency is that the definition of data collection should be broad. “When you have an eclipse chaser talking about what it feels like to stand in the shadow of the moon, for me, that is as relevant as the NASA footage,” she says. “It’s a different way of reading that environment, of reading that entity, of reading that body. And it becomes a way of also bringing it a little bit closer, and also making it less distant, I think.”

For more by Rohini Devasher, check out her website and Instagram. Find more about One Hundred Thousand Suns, including trailers, here.

*

Featured image: Still from “Paradigm 2 Twin Suns” in One Hundred Thousand Suns (2022) by Rohini Devasher.

All images courtesy of the artist, The Open Data Institute, and PR representative Binita Walia.

Share this Post