An NFT is like a hot mug of eggnog. Mention it to a group, and you can expect a few staple reactions: “hate it,” “love it,” or “what even is that, anyway?” (maybe even, “oh, my friend makes his own”).

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a unique, one-of-a-kind unit of data. This unit of data is a record, proof of ownership and authenticity, that’s kept on a secure digital ledger called a blockchain. It corresponds to some kind of digital asset, like Nyan Cat, or your very own Bored Ape, or a video clip of LeBron James dunking a basketball. An NFT basically says “this is without a doubt the original”—like with a painting, many prints can be produced, but there’s only one “real thing,” which you either own or you don’t. And people like to own things.

The dizzying prices for which NFTs can sell has generated heaps of media attention, as have the types of NFTs for sale (there’s an NFT of Lindsey Lohan’s fursona?? It really is the end of days!!). Debates have escalated over NFTs’ ability to provide creators with a platform and income versus their ultimate futility as a flash in the pan. But overshadowed by the screaming and crying about a stranger buying Taco Bell’s NFTs (which include a gif of Newton’s Cradle but it’s tacos), are quieter but crucial conversations about artistic merit many NFTs warrant.

Sarah Friend’s work is an excellent example. Friend is an artist and software developer who’s worked in the blockchain industry since 2016 and in 2018 was named one of Canada’s 30 developers under 30 (and she was kind enough to chat with Art the Science back in 2019). When we speak this time, she’s hailing from the Starship Enterprise (okay, it’s a Zoom background).

“It’s been super hyped. It’s been insane,” Friend says of NFTs. “I make NFTs, and I want the world to shut up about NFTs half the time.”

Friend’s NFTs probe what exactly NFTs are and what they represent for us culturally. NFTs are meant to be, as Friend puts it, “this sort of system of ownership and assets”—like with cryptocurrency, you’re supposed to hold onto them, hoping they’ll go up in value. They reward the self-interested and individualistic user.

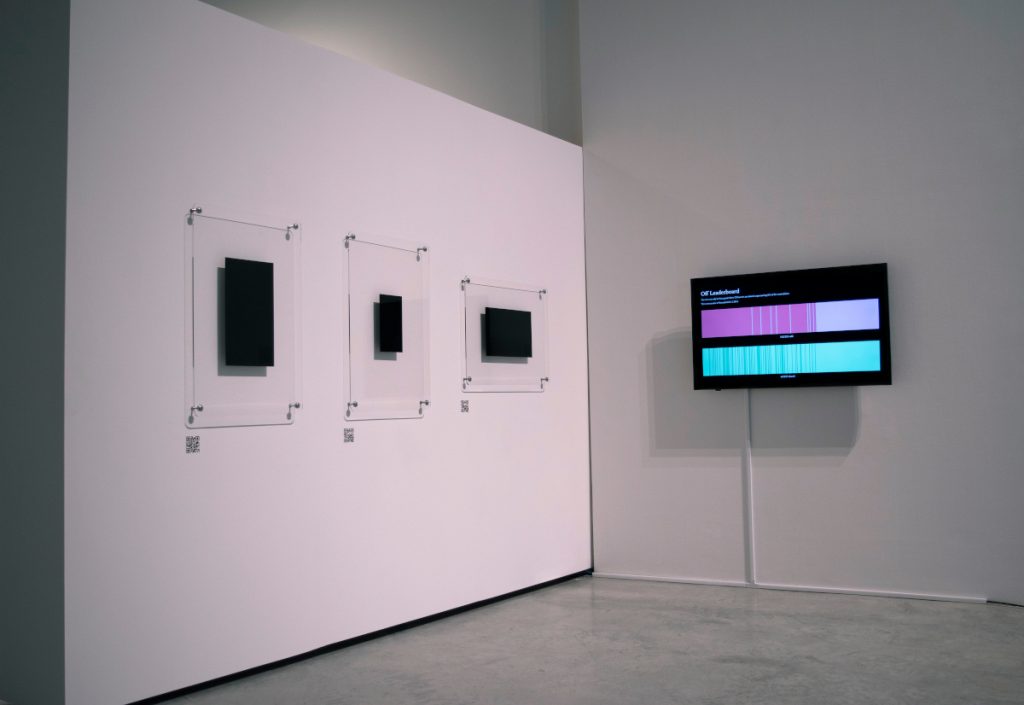

Now, what if we assume instead the user is collaborative and mutualistic? Take Friend’s project Off, an artwork, artist edition, and multiplayer game. The artist edition consists of 255 NFTs displayed on the project’s website as a series of black rectangles labelled as devices: BlackBerry Z10, Dell XPS 13, Samsung Galaxy A50. The black images are the same dimensions as the devices. Each piece has a “public” image, the black rectangle you see on the website, and a “secret” image, which you get by email if you purchase a piece.

In each secret image is a bit of an encrypted message and a bit of the key you need to decode it. Across the 255 images is an essay waiting to be uncovered, and you need 2/3 of the key to decrypt it. The NFT owners must therefore work together, sharing freely their NFT’s “secret,” so the group can read the essay. It incentivizes cooperation, simply asking people to not behave selfishly. You can think of Off as “a massively multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma,” as its website states.

“Off sort of calls upon people to see if they will work together at a large scale to solve the puzzle that is really a benefit to everyone to solve. There’s sort of no real reason not to do it, except…the normal logic of NFTs, which is quite powerful,” Friend explains to me.

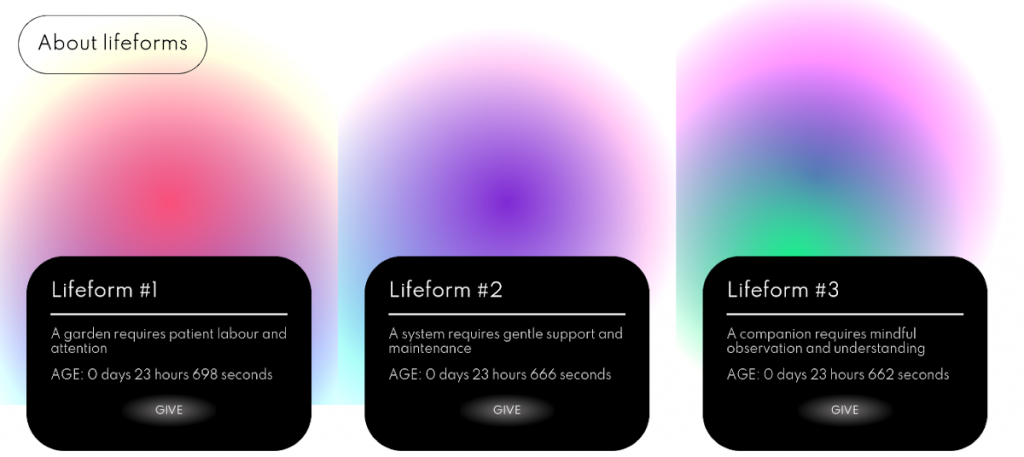

Hours before Friend and I chat, she launched another project, Lifeforms. These NFTs “die” if you don’t give them to a new caretaker within 90 days. (Like Off, which has physical versions that can hang in galleries, Friend made some physical versions of Lifeforms as well, which she describes as “lumpy, squishy, kind of cuddly phones.”)

“The common thread is making NFTs that don’t quite work, unless in some way you give them away, or share them,” Friend tells me. “And the reason I’m interested in this kind of system is that I actually think we’re surrounded by this kind of system all the time. What is the climate crisis but a collaborative coordination game that we are failing to play?”

A natural point of annoyance for Friend and, I imagine, for many artists is that what gets overlooked about NFT art is, often, the art. “I find it a little frustrating to see…article after article about NFTs, but they never talk about the art,” Friend tells me. “They usually talk about how much they sold for. I’ve also had the experience where an exhibition that I’m in has been reviewed or written up in a publication, but they don’t talk about the art at all, what the art is about, whether the art is good. They just list the prices.”

Friend thinks the final form of Off will take shape after the game has played out, and the attention has died down. She tells me that she’d like to write a retrospective, where she interviews the collectors, as a way of giving the public insight into the dynamics, relationships, and strategies that formed along the way. “I feel like its final form is going to probably be an essay, and I realized that kind of recently,” says Friend. As for Lifeforms, she teases there might be more coming.

And what about the future of NFTs? “I mean, the way these things go is things get blown out of proportion, and then they fall out of attention. And then they find their real home someday, you know?” Friend tells me. She also points out that precedent exists for NFT collecting, like marketplaces for digital goods, marketplaces for game items, marketplaces where you can buy, for example, a World of Warcraft character that someone else has gotten to a certain level.

I ask Friend if she predicts that, a decade from now, people will still be collecting NFTs. She thinks for a moment and responds, “Yeah, I do. But I think it might be much more quotidian and less interesting than it is now, in some way.” She adds, “I think it will be around, and it will somehow be much, much more boring than it seems at the moment.”

For more about Sarah Friend, visit her website, Twitter, and Instagram.

*

All images courtesy of the artist.

Share this Post