Name: Vance Williams

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

I wanted to be scientist from a young age. In my early teens, I was captivated by the images of science, especially photographs of planets, galaxies, and nebulae. My career path eventually led to chemistry, but I retained this aesthetic sensibility. Although chemistry is a very visually oriented discipline, we rarely harness photography when trying to engage broader audiences. This stands in stark contrast to other fields, such as astronomy and biology, and has always struck me as a missed opportunity. When I became involved in public outreach, it was natural to use pictures from my own research into liquid crystals.

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

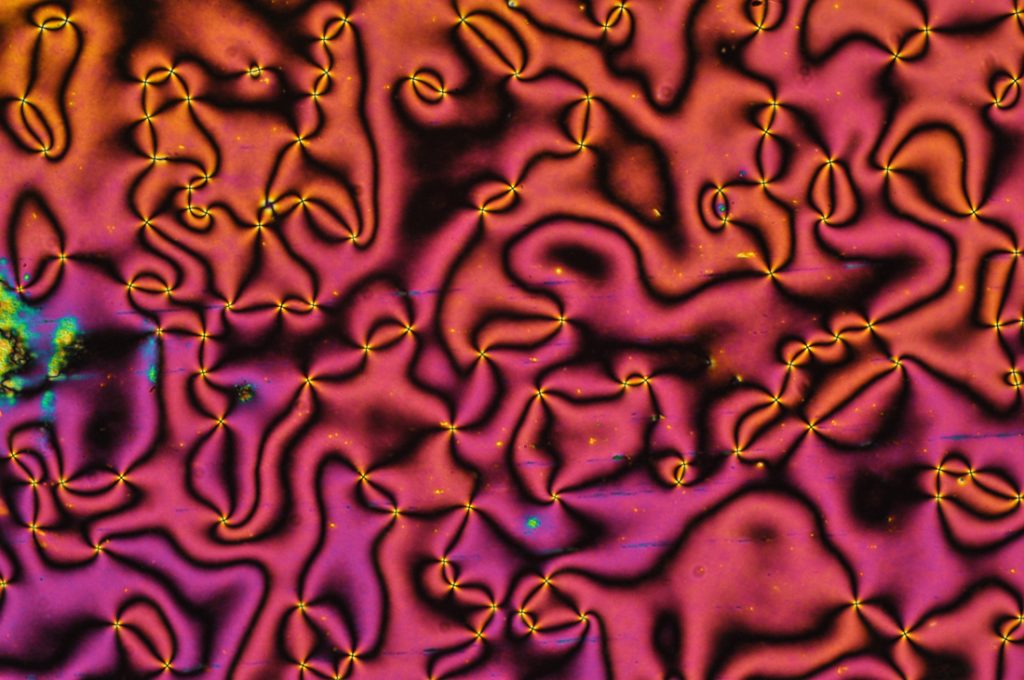

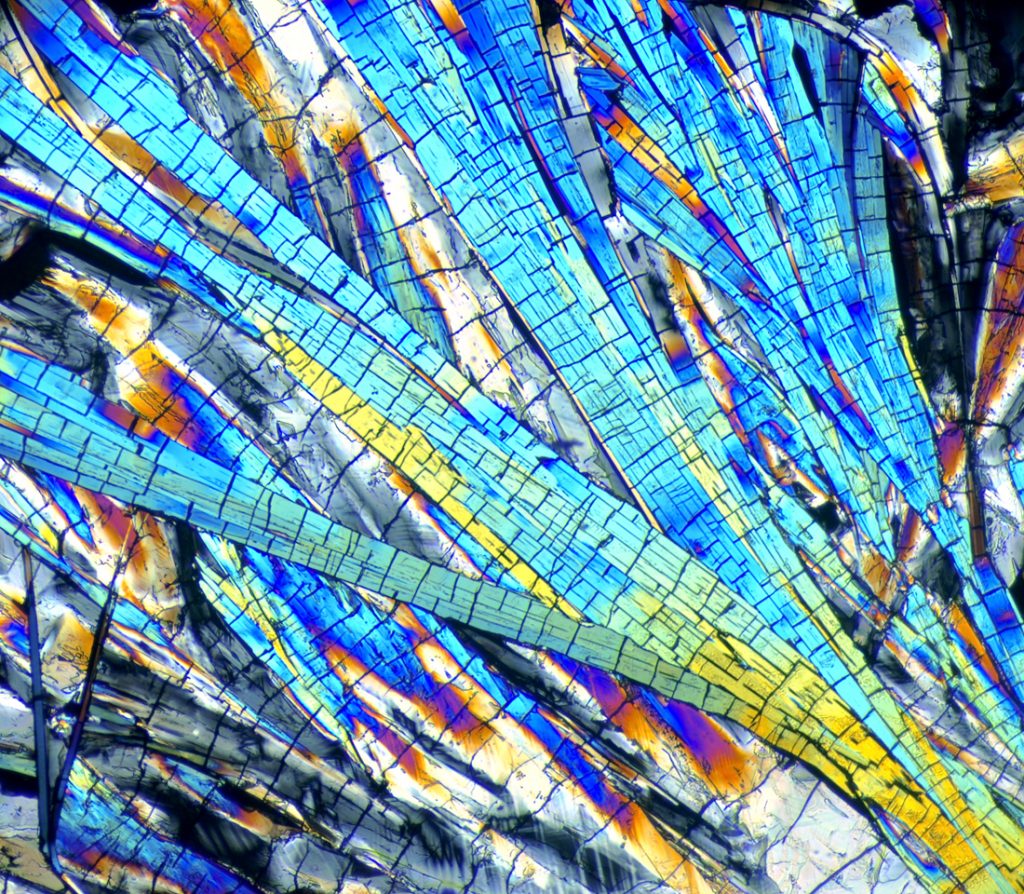

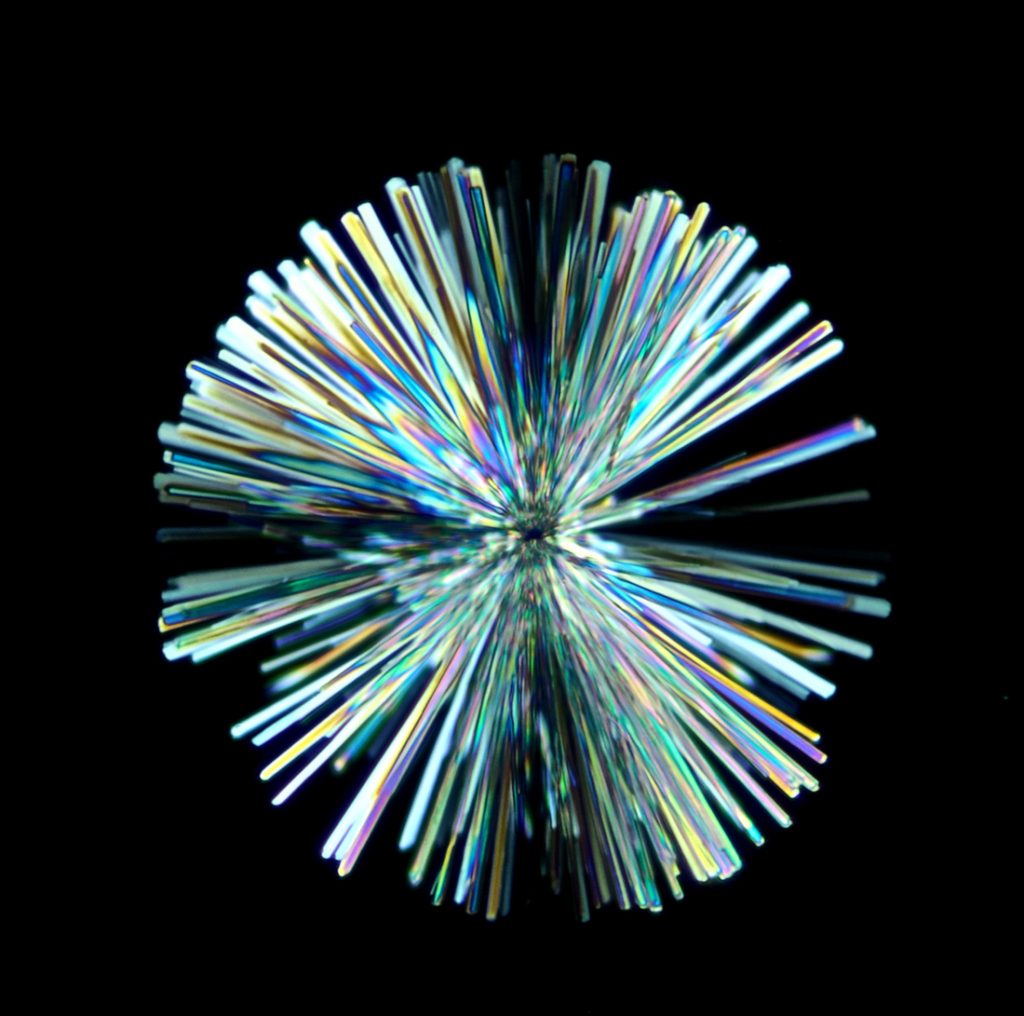

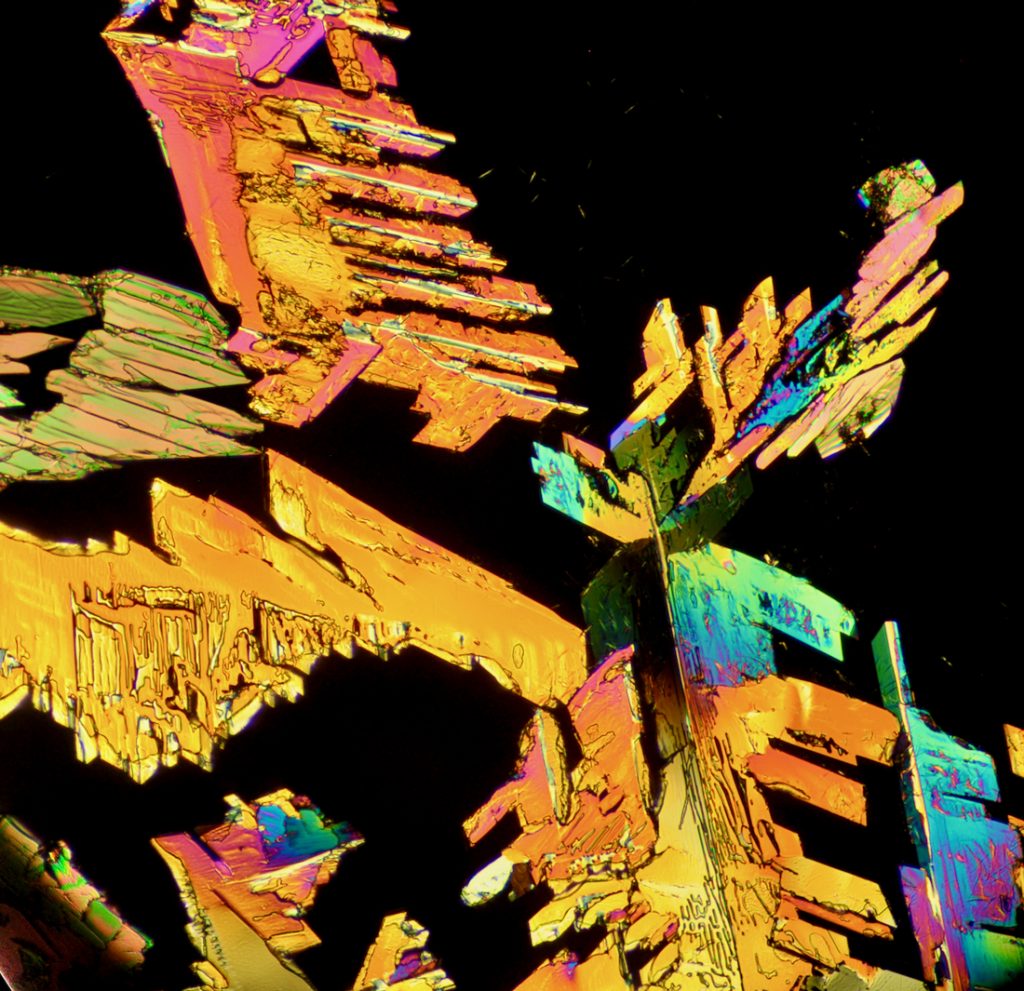

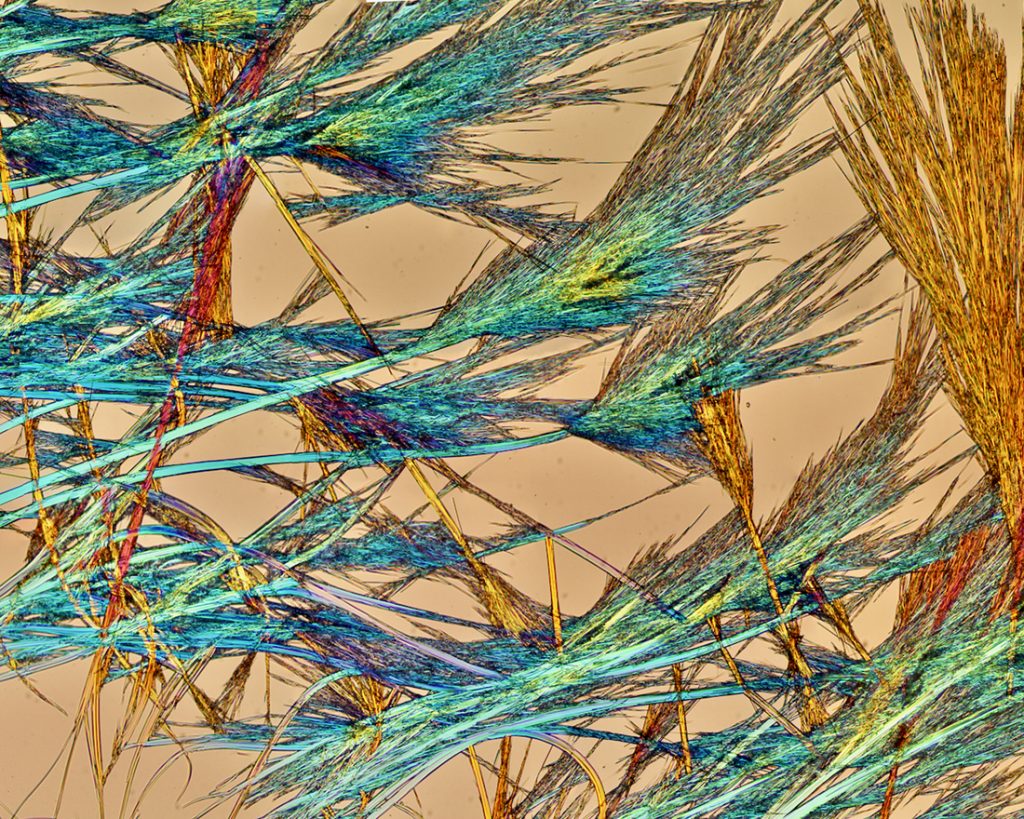

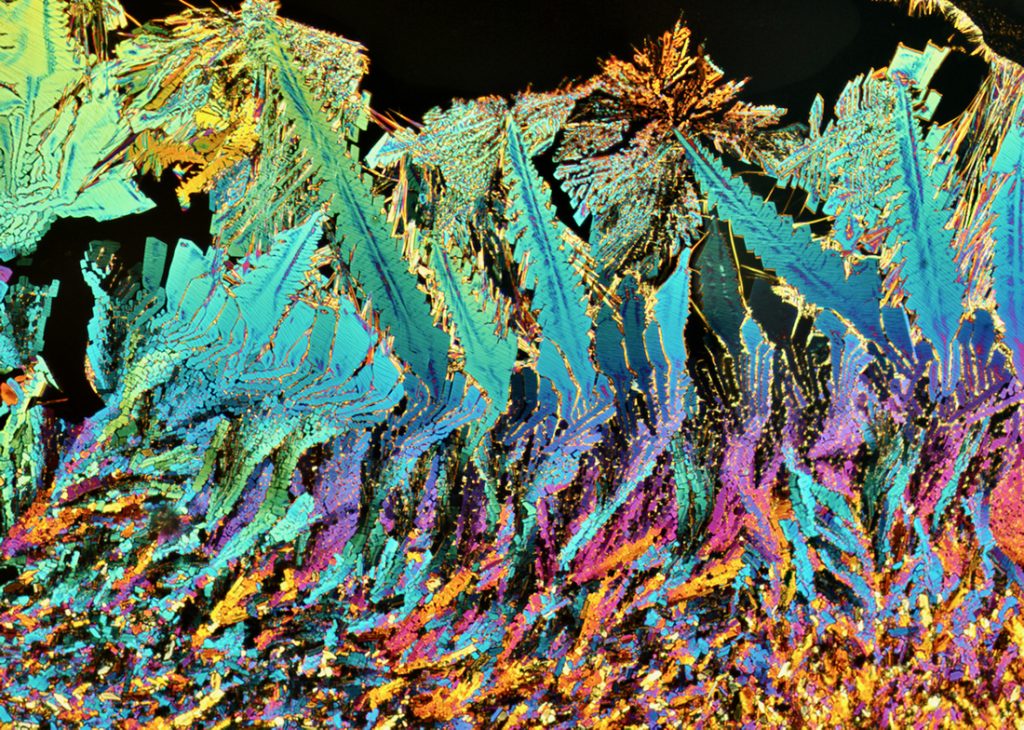

My art follows directly from my day job as chemist and materials scientist. A key tool in my research is polarized optical microscopy, a technique that I use to probe the molecular ordering within a material. It also happens to yield beautiful images. Even relatively bland white solids reveal a riot of color when viewed by this method. While my subjects are chemicals from my lab, I use images of their crystals to initiate conversations on a variety of topics, from ecology, to biology, to physics. Although I lack any kind of artistic training, decades as a chemistry researcher and teacher deeply inform my practice.

What materials do you use to create your art works?

I initially used liquid crystals from my research group. As I started pursuing non-specialist audiences, I turned to images of more familiar chemicals, such as caffeine and aspirin. Recently, I’ve photographed molecules that can serve as portals for teaching chemistry. These can be fairly innocuous, like cholesterol, niacin (vitamin B3), or menthol (the molecule that gives mint its flavour), but they can also be more topical or contentious. Photographs can be used to help challenge pervasive societal assumptions, such as the word natural indicating something is safe, whereas unnatural indicates something is unsafe. Rotenone, a naturally occurring insecticide that is used in organic farming, is toxic to fish and humans, as well as the target bugs.

“Photographs can be used to help challenge pervasive societal assumptions.”

Vance Williams

Recently, I’ve begun to use these images in chemistry storytelling. For example, 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid, despite its dry name, is a fascinating molecule that is responsible for the blue of denim pine. With the help of warming temperatures, pine beetles have decimated coniferous forests throughout western Canada, leaving behinds dead trees that have been stained blue. These trees are harvested and their lumber is sold as denim pine. When the beetles burrow into trees, they bring with them a “blue stain fungus” that plays a large role in killing the host tree. The fungus uses the dihydroxybenzoic acid to bind iron; these iron complexes are thought cause the wood to turn blue.

Artwork/exhibition you are most proud of:

In early 2018, I was contacted by Richy Carey, who was the UNESCO City of Music Artist in Residence for Glasglow. Carey was working with Scottish school children to create film and sound performances based on liquid crystals. He had found my videos on YouTube and asked if he could include them in an interactive audiovisual public art installation. “The Twist (is that you’re just like me)” was featured in the Children’s Exhibition at the Glasgow Tramway in the summer of 2018 and incorporated my videos along with performances from Carey’s young collaborators. The exhibition received approximately 6000 visitors over six weeks.

My participation in this project was admittedly minor; Carey, as an artist and educator, provided the vision and executed the work. This project nonetheless is my favourite because it exemplifies the ability of a science-art collaboration to function as a form of science communication.

“This project…exemplifies the ability of a science-art collaboration to function as a form of science communication.”

Vance Williams

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

Scientifically, my biggest influence was Robert Lemieux. More than a quarter century ago, Bob introduced me to the world of liquid crystals and microscopy. I never intended to study materials science; I was an unemployed chemistry undergrad who just happened to knock on the door of a new assistant professor. A summer job turned into a PhD and a lifelong fascination for the ways in which molecules organize themselves into materials.

Another early influence was Alfred Bader. Bader had been a graduate student in the chemistry department at Queen’s University back in the 1940s, before he went on to found the Aldrich Chemical Company (later Sigma-Aldrich). Bader was not just a chemist, entrepreneur, and philanthropist; he was also a passionate art collector and amateur historian. When I was a graduate student at Queen’s, Bader would periodically visit and give lectures on the interface of science and art. He made it clear that these disciplines were profoundly intertwined.

I have also been inspired by the work of Felice Frankel, a photographer who has spent much of her professional career working with scientists at institutions such as MIT and Harvard. Her collaborative projects translate elegant scientific experiments into beautiful art. In addition to being a gifted artist, she is a scholar, a teacher, and an author. Through her books, classes, and workshops, Felice has played a vital role in fostering the practice and popularity of science-based art.

For more by Vance Williams, visit his website, Instagram, Twitter, or YouTube channel.

Share this Post