Name: Vera Scekic

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

In retrospect, the science came first. I spent much of my childhood roaming a field of grass and woods at the end of my street in search of insects, showy flowers, and rocks with crinoid fossils. (My home sat atop the Niagara Cuesta, and there was a quarry nearby.) Out of these “specimens,” I fashioned crude terraria populated with rubber spiders purchased from gumball machines. One especially memorable early June afternoon, I discovered a plate-sized Cecropia moth pressing its wings against a jar into which I had dropped a brown cocoon stuck to a twig the night before. The astonishing and—to my eight-year-old mind—inexplicable transformation sparked an enduring curiosity to apprehend the world: to first ask, what do we know, and, as I grew older, how do we know what we know (in terms of the methodologies and systems we use to construct our explanations.)

“I spent much of my childhood roaming a field of grass and woods at the end of my street in search of insects, showy flowers, and rocks with crinoid fossils…I fashioned crude terraria populated with rubber spiders purchased from gumball machines.

Vera Scekic

Classes in art, history, philosophy, literature, linguistics and, yes, math and science, filled the ensuing years. With an array of texts, problem sets, field notes and museum visits providing hindsight, I now see art and science as complementary modes of inquiry, adjacent means to answering what and how, and, in the process, leaving a record of who Homo sapiens perceive themselves to be at a particular notch in time.

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

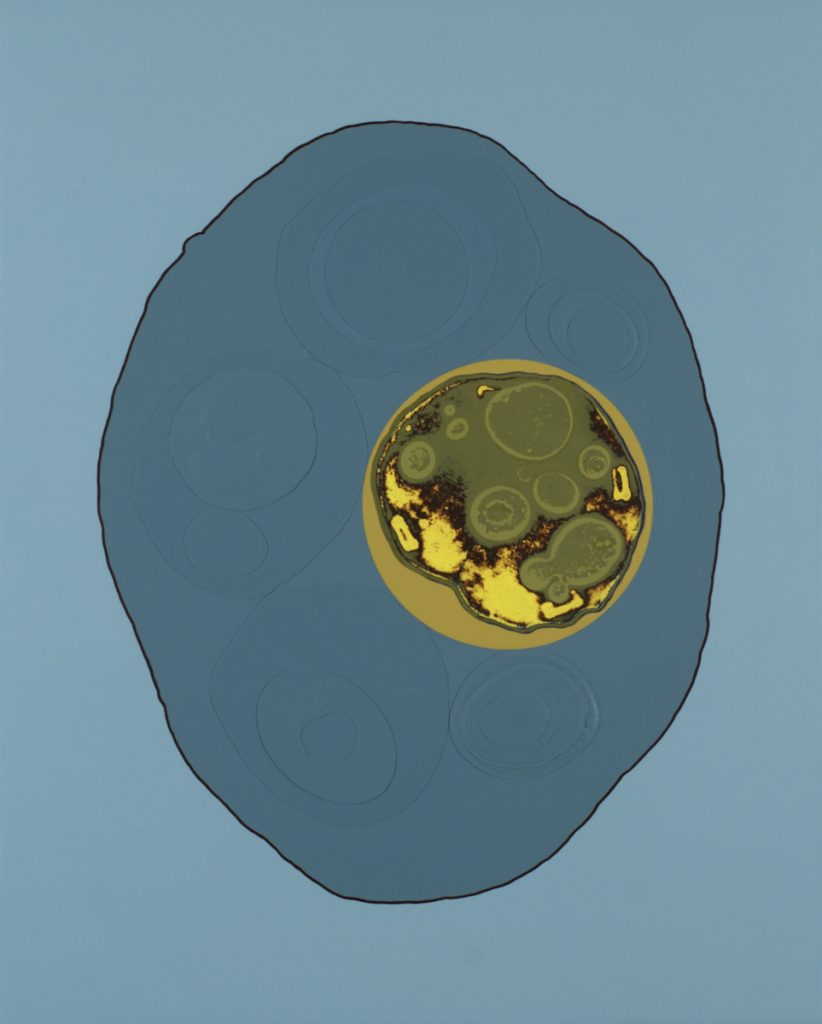

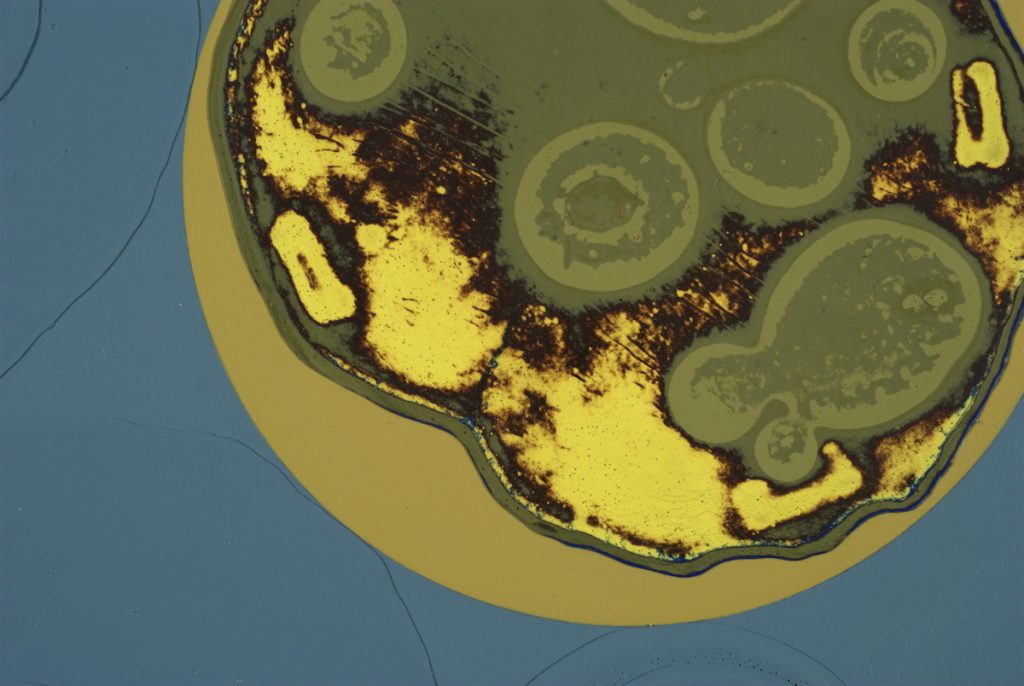

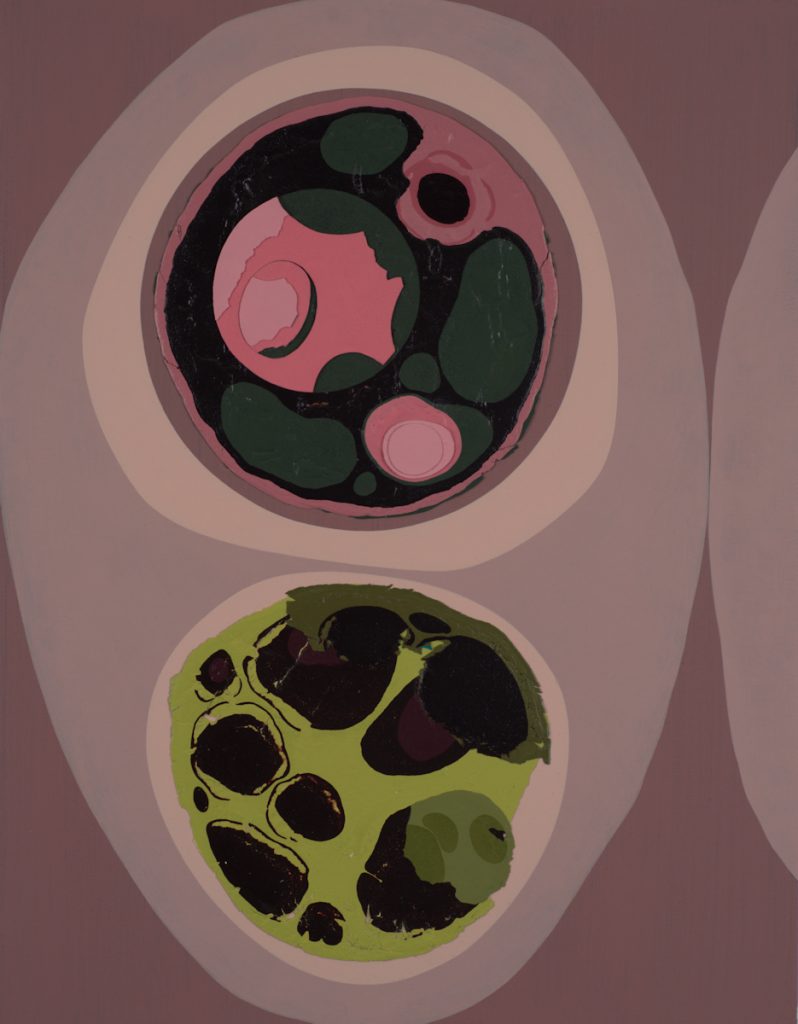

I’ve bored my family many times waxing enthusiastic over a landforms map or an article announcing the first direct observation of gravitational ripples emanating from a 1.3 billion year-old merger between black holes. But my primary obsession is biology: evolutionary, ecological, developmental, microbial, genetic. All facets of the discipline—its questions, concepts, methods, and imagery—inform my practice in overt and subtle ways. My studio and nightstand hold more books about biology than any other subject.

What materials do you use to create your art works?

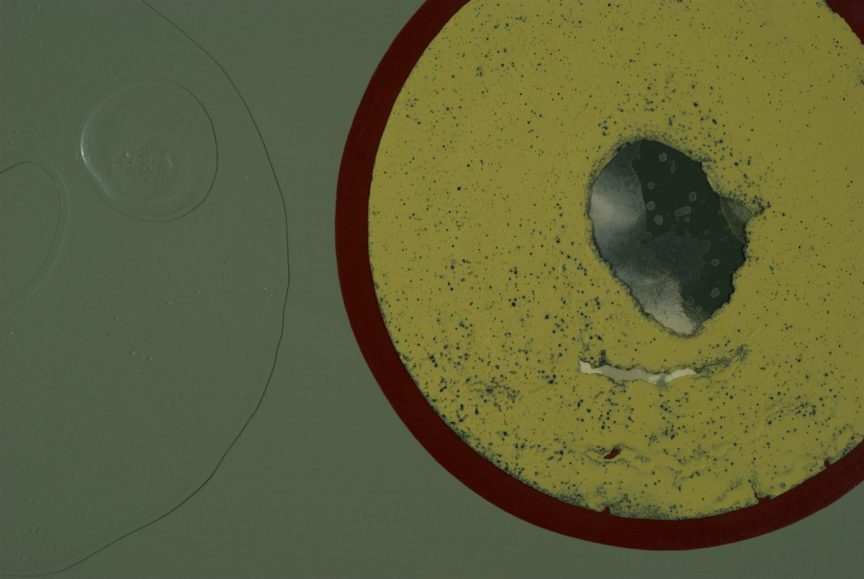

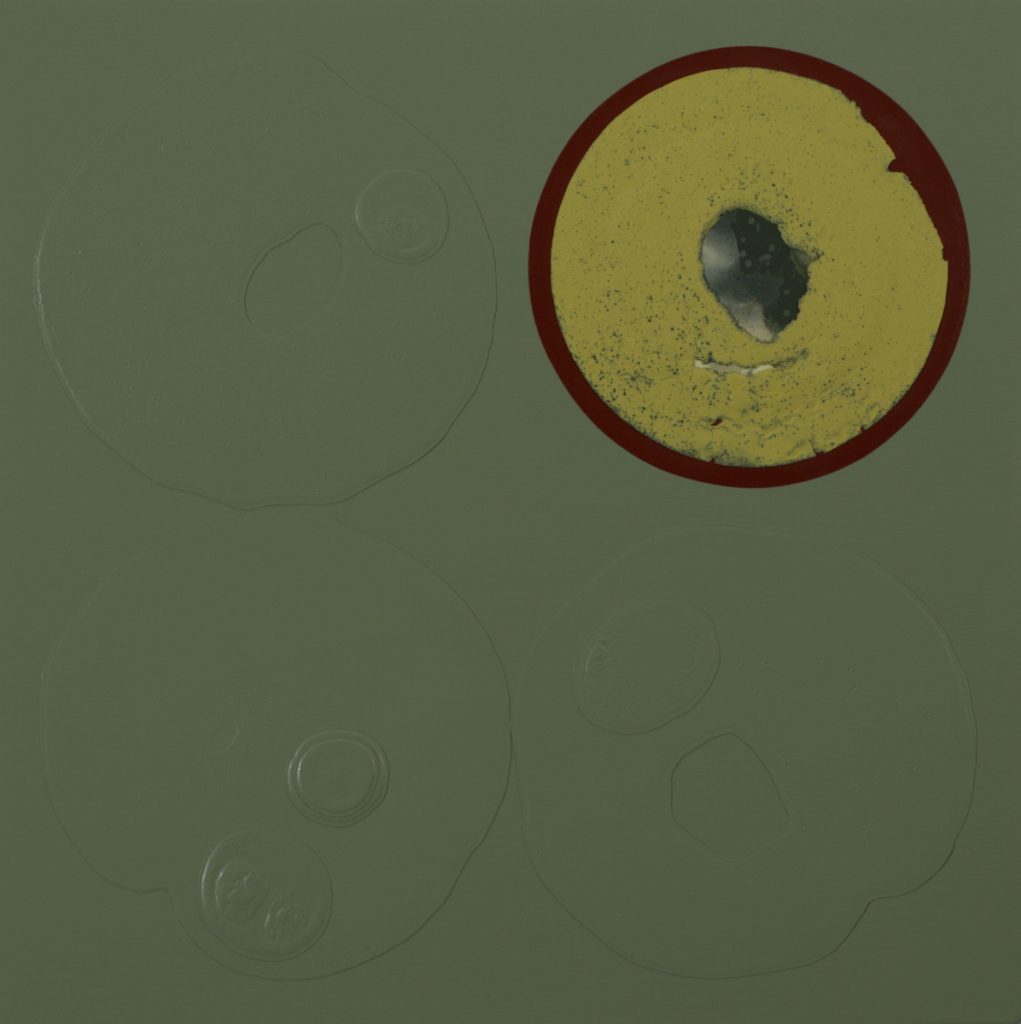

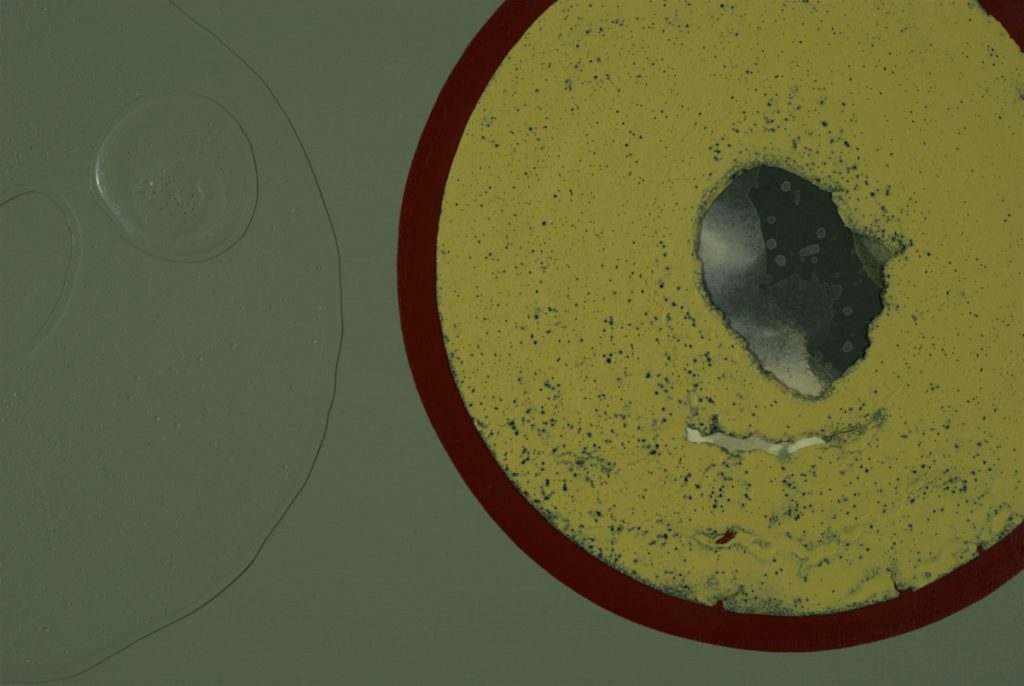

I’ve used materials as disparate and ordinary as Styrofoam cups, metalized tape, and drafting film to create my works. For the past several years, I’ve trained most of my focus on an open-ended series of paintings that uses the cell as its conceptual foundation. The paintings are constructed using a multi-step process that begins when I mix acrylic paint with various thinning agents and pour the liquid onto drafting film. Once the paint pours have dried (sometimes using a hair dryer to force rapid drying and create a fractured surface), I cut them out of the film. The shapes are then coated with additional layers of paint, sanded, re-coated and sanded again, then peeled from the film. The resulting paint fragments are spliced, layered, and arranged onto a wood or canvas support.

Artwork/exhibition you are most proud of:

Two exhibitions compete for first place: Bilateral Symmetry (Hyde Park Art Center – Chicago), a gridded installation of 390 circular paint pours that covered two facing walls 18 feet high by 15 feet wide, and Naturally Unnatural (Birmingham Bloomfield Art Center – Michigan), which featured 23 paintings from my cell series surrounding Microarray, a floor-based installation made from 1,440 Styrofoam cups and paint.

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

This list could fill a page, so I’ll select five from each category. In alphabetical order, scientists: George Church, Jennifer Doudna, Lynn Margulis, Ernst Mayr, E.O. Wilson, Carl Woese; artists: Lee Bontecou, Vija Celmins, Tara Donovan, Mary Heilmann, Roman Opalka.

Is there anything else you want to tell us?

In addition to my visual art practice, I direct a contemporary art gallery, OS Projects, located in Racine, Wisconsin.

Find out more about Vera Scekic from her website.

Share this Post