Marine geophysics buff, printmaker, science communicator—Ele Willoughby is all of these things and more.

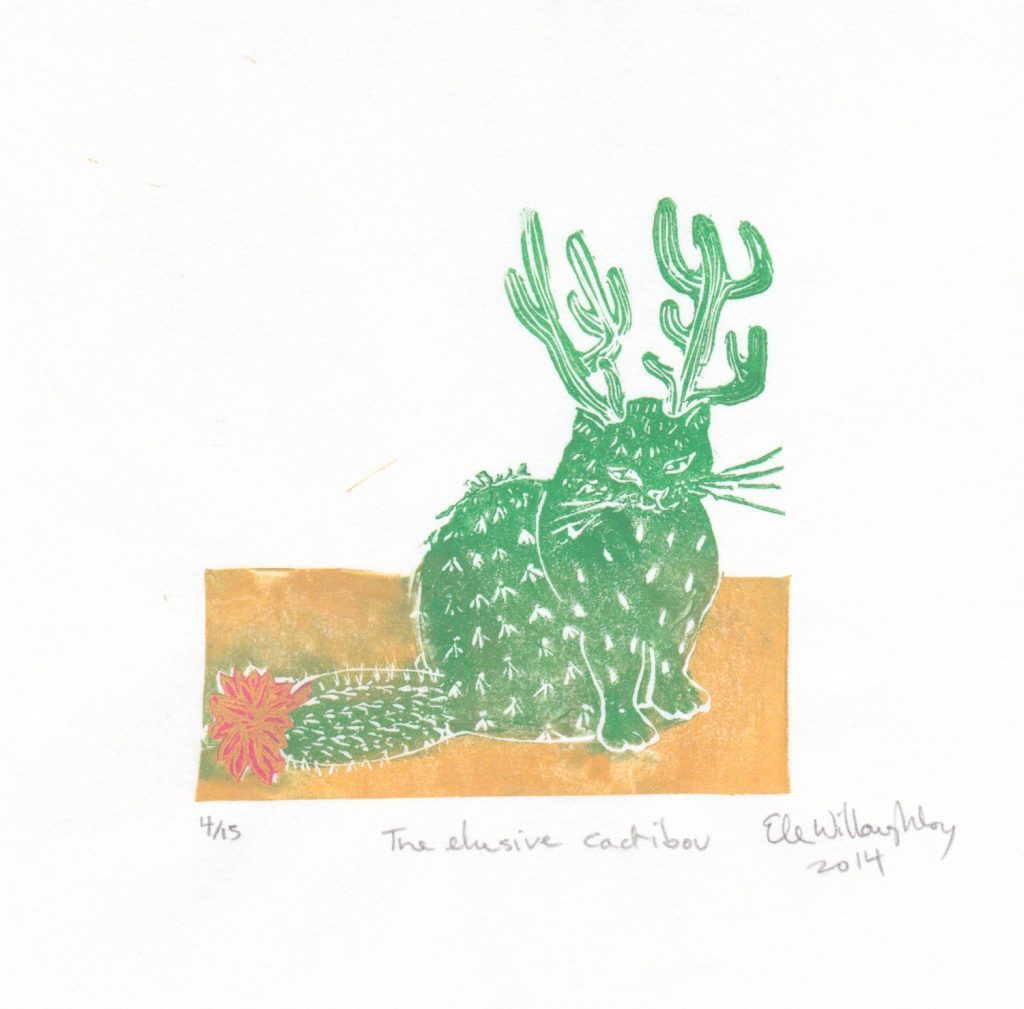

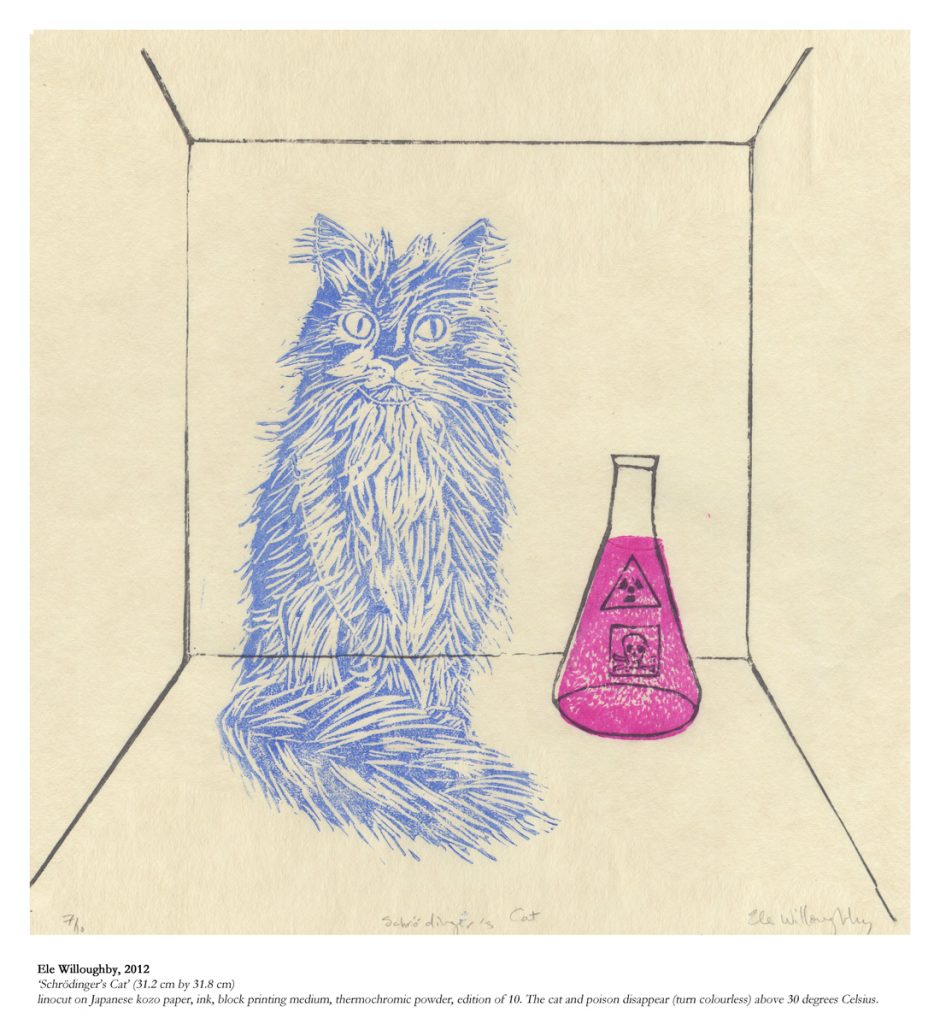

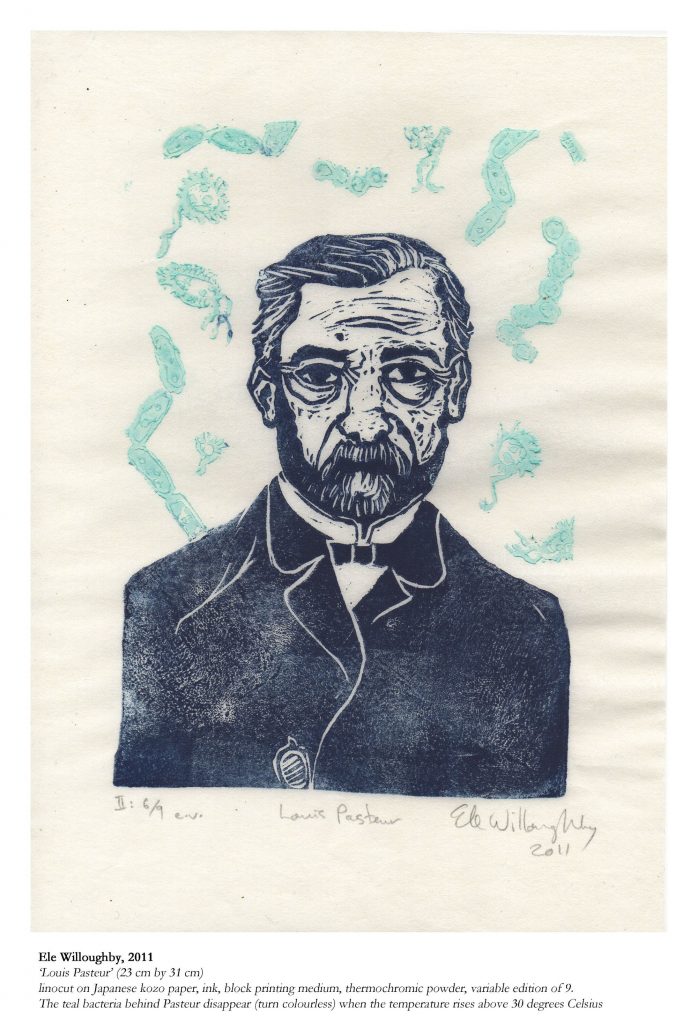

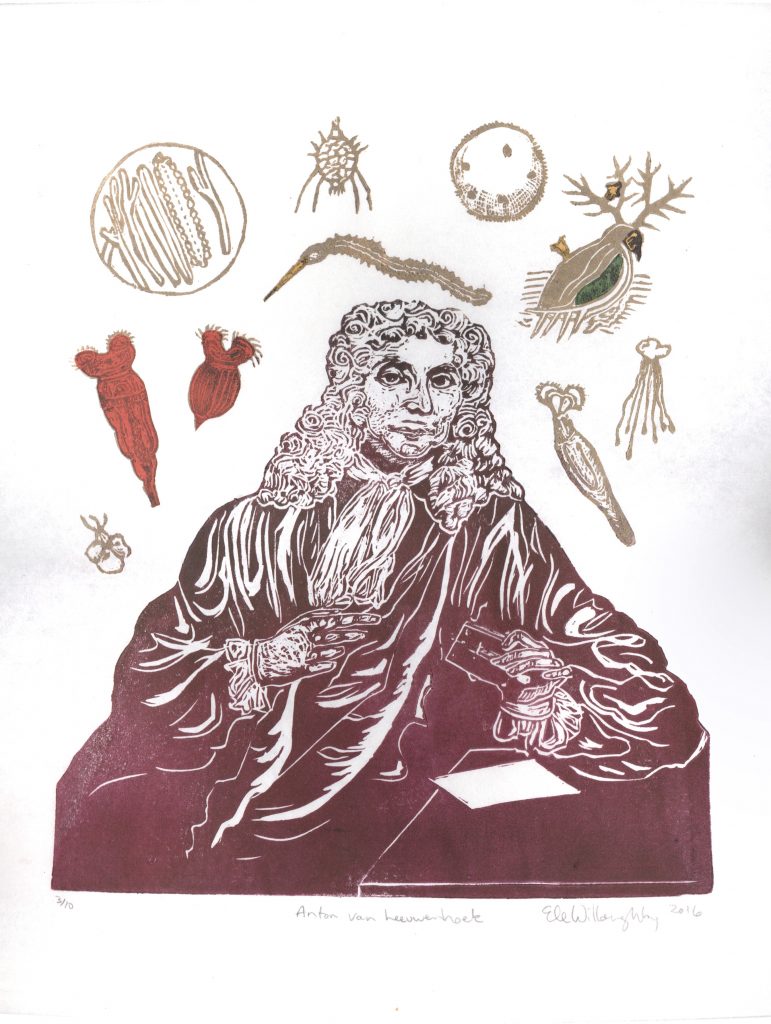

Using a mix of techniques, the sciartist showcases endangered species, microbes, historical figures from science, and more. She brings them to life in her colourful images and prints, offering a new look at Schroedinger’s Cat, Louis Pasteur’s bacteria, and everything in between.

Here, Willoughby shares thoughts on her creative process, her winding career path, and the notorious divide between art and science.

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

I have always loved both art and science. As a child, when people would ask me what I would do as a grown-up, I said, “Something with math,” and I did grow up and study physics. But I took art throughout school and took class at the Art Gallery of Ontario when I was young.

When I reached university, I felt I had to choose between these two loves. I have a doctorate in physics—specifically, marine geophysics. Throughout grad school I spent my spare time making art and taking art courses. I was recruited as a TA for a physics course for arts students, which focused my thinking on how to communicate scientific ideas to people who are interested but might lack the mathematics or the background to easily understand.

As a post-doctoral fellow in marine geophysics, I started to feel that I was missing something and began pursuing art more seriously. I started a small business and began selling artwork, at first in order to fund my art supply habit, but it grew. My art featured a lot of natural history. I found many other artists who had backgrounds in science and began to use my art as a means of communicating science to a wider audience. Since then I’ve worked to try and pursue both art and science or to combine the two. Now I am primarily employed as an artist.

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

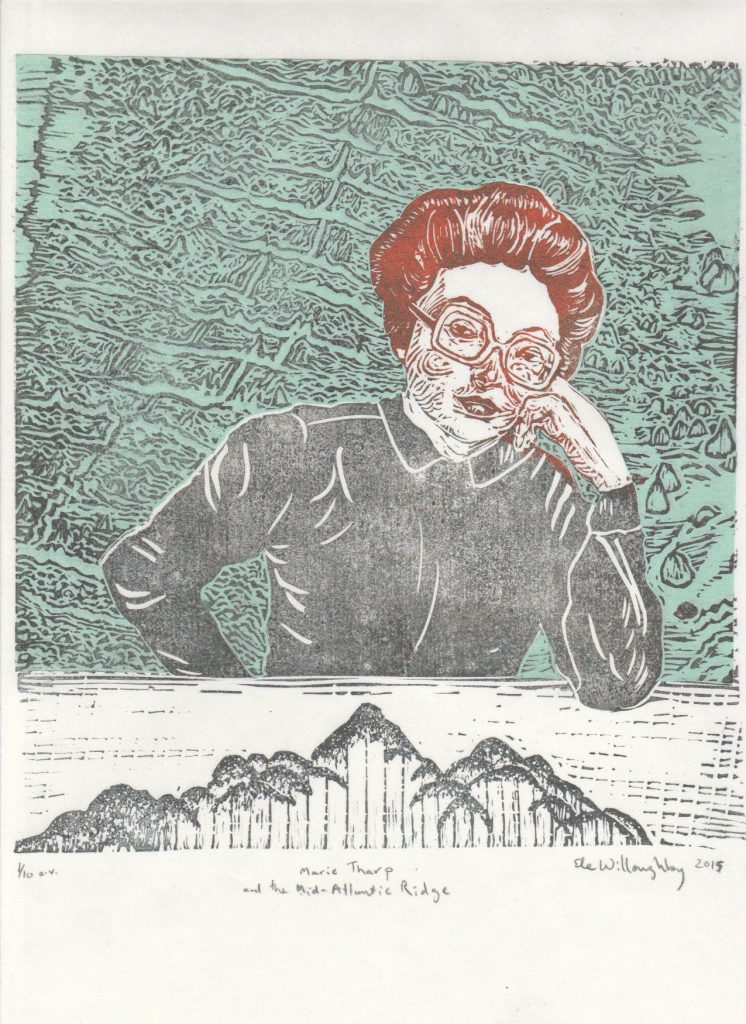

I explore a few different scientific themes in my work. I have an ongoing portrait series of figures from the history of science along with imagery related to their work. I’m particularly interested in telling a fuller story and returning those who have been too often forgotten like women and under-represented groups. There are a lot of physicists, Earth scientists, computer scientists, mathematicians and chemists in this collection, but biological and medical scientists figure too.

I think of my prints as a sort of wunderkammer and I have a large collection of natural history, especially animals. I’m fond of lesser-known creatures which often leads to highlighting endangered species or thinking about ecology and biodiversity. I have prints depicting the microbes, extinct animals, and a lot of marine invertebrates (some of which I have seen working as a scientist at sea). In parallel with this, I am working on a collection of imaginary or hybrid creatures including imaginary natural history, which is a way to explore the extraordinary diversity of real animals and their roles in the environment.

You’ll also find concepts from astronomy, physics and chemistry in my work. Sometimes I employ the physical sciences in the construction of the artwork, making interactive works, for instance with colour-changing thermochromic ink or electrically-conductive ink and electronics.

What materials do you use to create your artworks?

I work primarily as a relief printmaking. Most of my work is linocut prints which I carve in reverse in linoleum (or similar but softer artists’ materials) or occasionally wood. I then ink these blocks and burnish Japanese washi papers onto them with a baren, a Japanese woodblock printing tool like a flat disk with a handle. I also do some collage with washi or other papers and multimedia work. I sometimes mix my own inks from pigments to get special effects like colour-changing thermochromic or UV-activated inks. I use electrically conductive paint or thread to encorporate electronics into artworks.

Artwork/Exhibition you are most proud of:

I think I’m most proud of Wunderkammer, a show in which I was both artist and curator. My own work (also called Wunderkammer) combined several of my interests and themes from my works. It is a large work (93 cm tall x 63 cm wide x 8 cm thick) broken into several wooden boxes like a cabinet, each of which features linocuts of different types of animals. There are hidden electronics to make the work interactive. Boxes feature: a lantern-fish with glowing lure (lit by LED), a bat, tapirs, assorted jellyfish and a ctenophore or comb jelly which flashes with stochastic patterns of flashing coloured lights (lit with LEDs), an octopus, an axolotl, radiolaria and a collection of insects. There’s an ear-piece hanging from the piece; it’s literally a fabric block-printed ear. If the viewer places the ear-piece on top of the cicada, bat or tapirs, the associated field recordings of their sounds will play on a hidden speaker.

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

So many! My collection of scientist prints gives a hint of my influences. I’ve noticed that without specifically planning to do this, many of the scientists I select from the history of science were also artists. I believe firmly that the art/science divide has been grossly exaggerated. I’m influenced by Ernst Haeckel’s artwork and believe that the ‘artforms in nature’ are both beautiful and should be a great part of our world and design (though it’s worth pointing out that some of his other ideas are terrible). I love the way early descriptive science was inseparable from its illustration, as in the work of Maria Sybilla Merian or Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, or even Mary Anning or Gerardus Mercator, and this can even be seen in more recent scientists like Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Is there anything else you want to tell us?

I also blog about the intersection of art and science at Magpie and Whiskeyjack.

Find more about Ele Willoughby on Etsy, Instagram, Twitter, or her blogs Minouette and Magpie and Whiskeyjack.

Share this Post