Name: Suzanne Anker

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

They arrived at the same time, in my childhood. The curious condition of a child’s imagination provided me with the opportunity to express my interest in world-making. In art, I would draw, make collages using magazines at hand, construct cardboard doll houses, and design little books. At school, I became the class artist. My pictures were hung up and I received much critical attention. In my kindergarten class, however, another classmate would tear down my pictures in frustration. I did tell the teacher who replied: “He is doing that because he likes you.” That was my first experience of how art had the power to communicate, even incite on a non-verbal level.

During playtime outdoors, I would roam the empty lot in back of my apartment building in Brooklyn. Filled with indigenous weeds and flying and crawling insects, the site became an area in which I could explore the teeming of life forms. Interested in hatching Monarch butterflies, I would collect milkweed and caterpillars and make shoe box homes for them. Bringing them indoors they soon became part of my apartment’s environment, even escaping and settling themselves on drapes to form a chrysalis and eventually hatch. The mesmerizing aspect of their transformation still gives me pause as an act of magic, even though there is a scientific explanation.

Another test I performed, with regard to magic and science, had to do with a peach pit which I planted in my grandmother’s garden. After planting the seed, I imagined that if magic was real, the seed itself would begin to sprout the next day as an answer to my queries. I went to bed dreaming that the seed would answer by beginning to grow into a peach tree. Needless to say, nothing happened, but I did not give up on the parallel fantasy world I created.

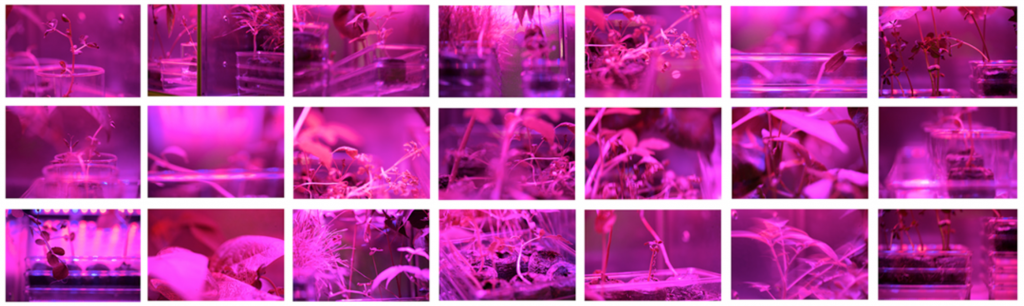

Astroculture (Shelf Life) | 2009

Astroculture (Shelf Life) (15) | 2009

Astroculture (Shelf Life) | 2009

Astroculture (Eternal Return) | 2015

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

The geological, meteorological, and biological sciences are sources for my work. From the 1970’s to the 1980’s the physical sciences figured prominently in my practice. At that time, I lived in Colorado where I was exposed to the Rocky Mountains, as well as extreme weather conditions and to the vast wonderment of snowfall. During this period I was engaged with casting paper in pulp form. The paper pulp for me was a matrix into which I could add pastels, glass, plaster, shell fragments, and more to create fossil-like amalgams. The powdery snowfall glistened with crystalline sparkle which I recreated with the use of shattered glass. From there I moved to Missouri and began visiting stone quarries in Indiana. The limestone too, embedded with fossils was a way to engage the geological presence of rocks. I began working with limestone runners, ready-cut stones that took the configuration of lumber. I employed these ready-mades to construct installations, and what I termed large-scale floor drawings. The limestone runners appeared to me as giant pastels, a form of gypsum, compressed to make marks. These works were subsequently exhibited at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and P.S 1 Museum in NYC.

The biological influence came in the late 1980’s when I began assembling objects and casting them in bronze. The strategy here was to fuse an object from nature with one from culture, hence creating a mutation that was naturally derived juxtaposed with a manufactured one. For example, a circular branch with a dog’s soccer ball. While exhibiting this work in galleries, I created a still life sculpture consisting of 100-year-old-eggs, a copper bowl, and small vases with kaleidoscopes attached. When on the viewer looked into the vases the resulting image was circular and reminiscent of a cellular form. That piece led me to the chromosome, a microscopic entity based on heredity, which I explored in silkscreen prints and sculpture for many years.

Origins and Futures | 2007

Origins and Futures (detail) | 2007

What materials do you use to create your artworks?

Whatever substances which seem relevant to the metaphors and other aesthetic requirements in my work become my material data bank. From photographic sets to rapid prototype sculpture to actual bones, fruits and insects, the array of materials borders on the ethereal while also employing the permanent. In the past, sugar crystals, plaster, bronze, iron, paper were source materials. Currently many of my installations employ objects from nature’s pantry: flowers, spices, butterflies, fruits and vegetables as well as manufactured fabrications: miniature toys, pastels, thread, glitter, rubber bands, beads among others. Materials have their own language and politic. While bronze seeks permanence, egg yolks display a transitory aspect closer to nature’s clock. Materials also represent cultural difference as well as global distribution. While specific cultures may

engage more prominently in ethic variations of food, most manufactured objects, crayons, party favours, Petri dishes, are distributed worldwide. As cultural difference fades into global homogenization, material’s signification is also altered in terms of meaning.

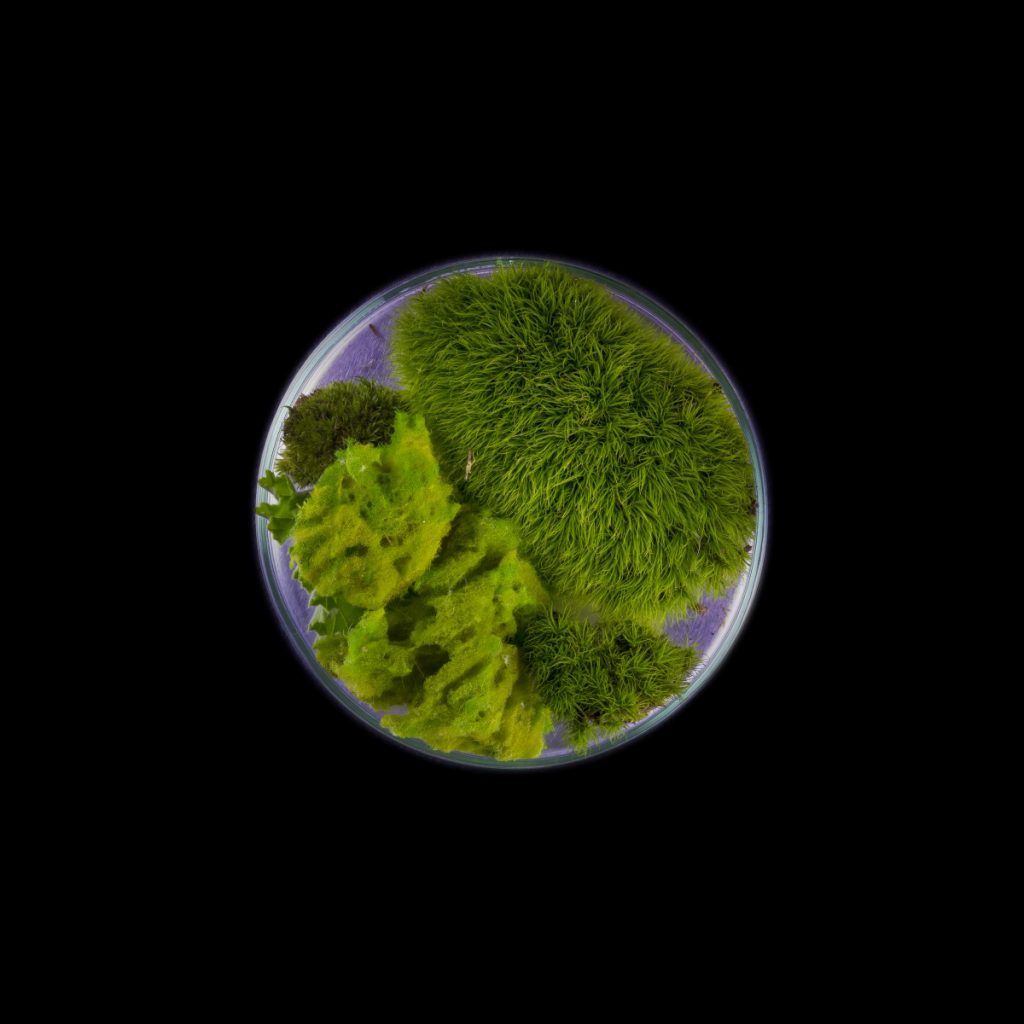

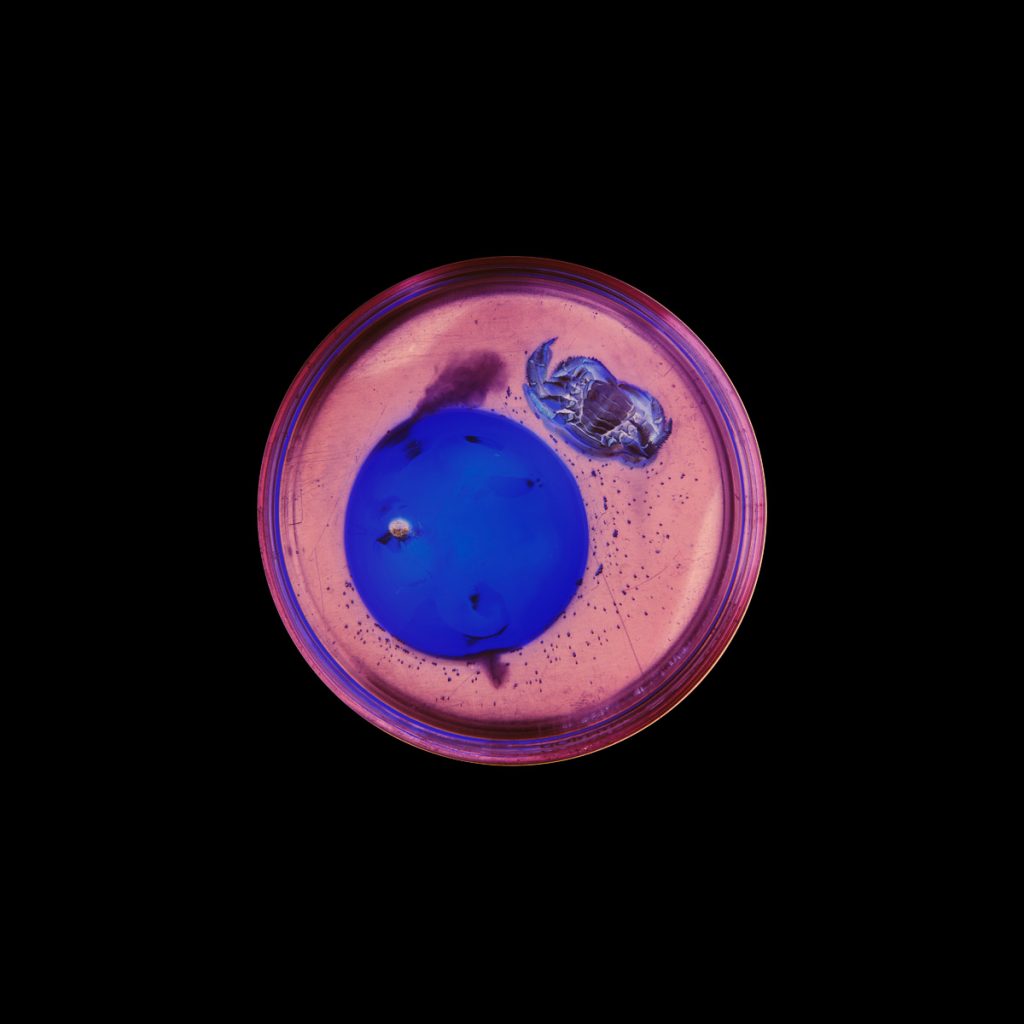

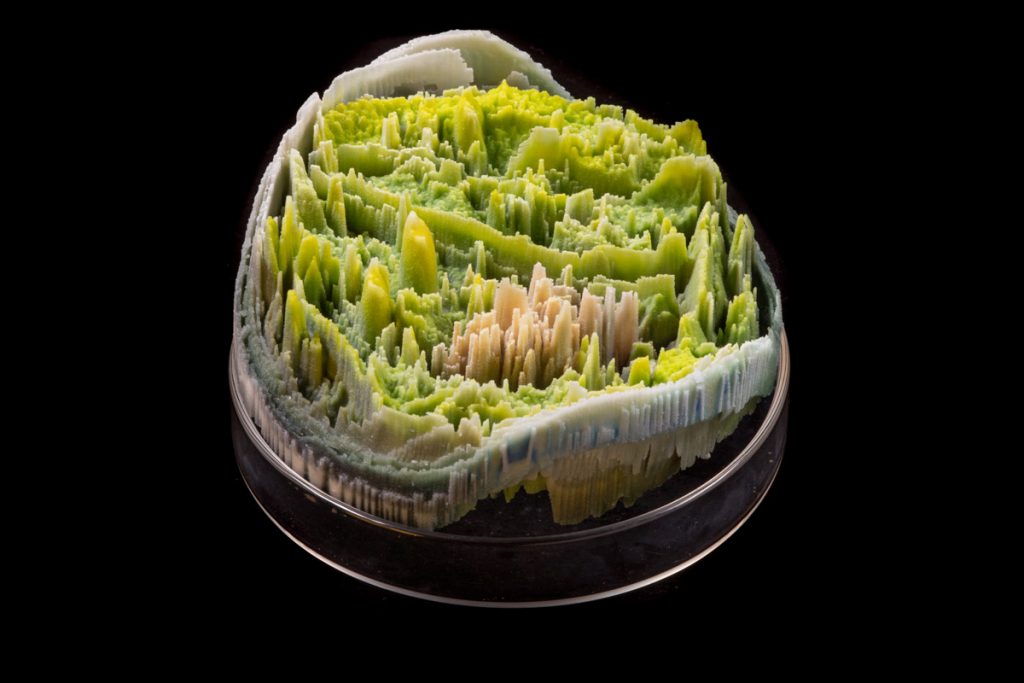

Vanitas (in a Petri dish) | 2013

Vanitas in a Petri Dish (17) | 2013

Vanitas in a Petri Dish (25) | 2013

Artwork/Exhibition you are most proud of:

There have been numerous occasions to exhibit my work in august institutions, private galleries, and alternative spaces. From the Devices of Wonder exhibition, curated by Barbara Maria Stafford and Frances Terpak at the J.P. Getty Museum in Los Angeles to Su Li’s exhibition The Future of Art at the Future of Today Museum in Beijing in China, each curated show contextualized my work in a domain representing either historical, conceptual or contemporary ideas.

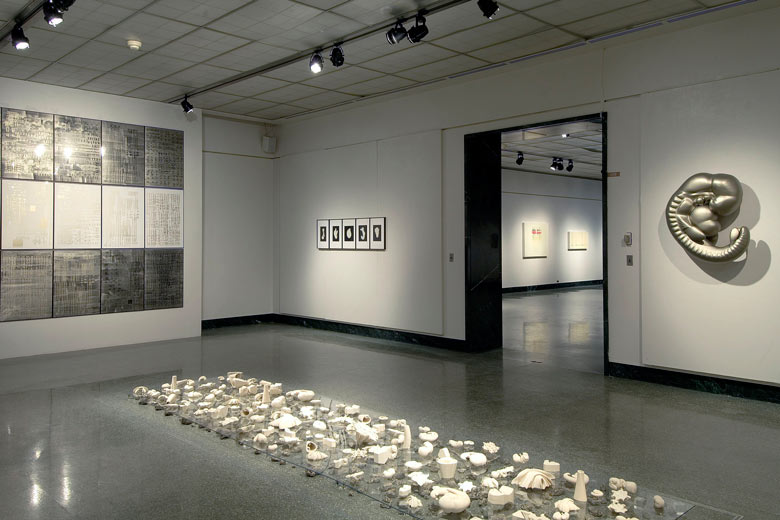

Installation view The Future of Today | 2015

Installation view The Future of Today | 2015

Detail of Rainbow Loom (2014) at The Future of Today Installation (2015)

Globale, curated by Peter Weibel at the ZKM, in Karlsruhe, focused on the ways and means technology has changed our perception of the future of our earth. The International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Cartagena de Indias, in Columbia, and curated by Berta Sichel was an extraordinary exhibition taking place in many of the buildings and public places of the city: the Palacio de la Inquisition, the Museo Naval Del Caribe, the Museo de Arte Moderno de Cartagena and La Casa Museo Arte y Cultura La Presentacion among others. Over one hundred works in all mediums and artists from many countries were represented. Themes included nature, politics, and gender among others. The Glass Veil, curated by Sabine Flach at the Charite Medical Museum’s Ruine in Berlin, allowed me to consider my work in a space that was not distinctly a white cube. Hovering between a bombed out edifice I displayed upside down parachutes and images from the museum’s collection. This exhibition was rife with political and social history. My exhibition (early in my career) at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis was also a seminal experience for me.

Rainbow Loom | 2014

Rainbow Loom (detail) | 2014

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

Of course there are many. Those artists that come to mind immediately are the late Helen Chadwick, Mark Quinn, Rosemarie Trockel, the late Robert Smithson, and Pierre Huyghe. Each of these artists formulated their work in unique ways that dealt with many of the concerns regarding the natural world. Helen Chadwick’s Viral Landscapes and Piss Flowers brought into view issues of contamination, gender, and bodily fluids. Mark Quinn’s incessant examination of his own body, the bodies of others and his concerns with immortality target the fragility of life itself. Rosemarie Trockel’s enormous data bank of images and processes (which included works by others in her solo exhibition at the New Museum in New York City) opens up a dialogue about influences and the way they can be reincorporated Robert Smithson’s non-sites and astute writing compared the mind to a geologic force of sedimentation. Pierre Huyghe’s use of bee hives and aquariums outfitted with anti-gravitational rocks are visually compelling.

RemoteSensing 18 | 2013

RemoteSensing 07 | 2013

As far as scientists that I have been inspired by the list begins with Darwin, whose revolutionary theories of evolution still absorb the reader today. Going against the dogma of his day and proposing a theory of species adaption and transformation is perhaps one of the greatest ways to observe the natural world. Barbara McClintock’s revolutionary research which employed touch as a way to ascertain genetic distribution and Rosalind Franklin’s groundbreaking crystallography photographs which were pertinent to the deciphering of the double helix are spectacular contributions to the field of scientific inquiry. Simon Fishel, a pioneer of IVF who worked with Robert Edwards at Cambridge to produce the first “test-tube” baby, Alexander Fleming’s unorthodox discovery of penicillin and Charles Vacanti’s experimental work in tissue engineering round out my list.

The Glass Veil | 2009

The Glass Veil (In and Out of Time) | 2009

Is there anything else you want to tell us?

My work consists of various subsets: teaching, public speaking, writing, and research in addition to art-making in various mediums. It is this combination of activities that continue to engage me and offer clues into the deep recesses of the ideas I wish to explore further. By moving back and forth between the literary, scientific, and aesthetic, a more complete engagement is attained to access and assess the combinatory practices necessary to make art. Speaking in public allows me to justify, and explain my ideas, recalibrate nuance, and pose questions that still need to be clarified.

Share this Post