Name: Michał Staszczak

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

I think when I was young, science was more important, but I have always had a very practical approach to it. As a child, and later at school, I loved doing experiments, testing different materials and tools. This hands-on experience was definitely more exciting than theory. I discovered my passion for art relatively late. I graduated from high school with a specialization in the renovation of architectural monuments. I learned a lot about technology, but I wanted to go further. That is why I chose to study sculpture at the Eugeniusz Geppert Academy of Art and Design in Wrocław (Poland). At present, I am a sculpture professor there, and I am happy to share my knowledge with others.

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

In my practice, I combine art with technology of metal casting, and recently, 3D design/printing. I am strongly inspired by biology and nature.

What materials do you use to create your artworks?

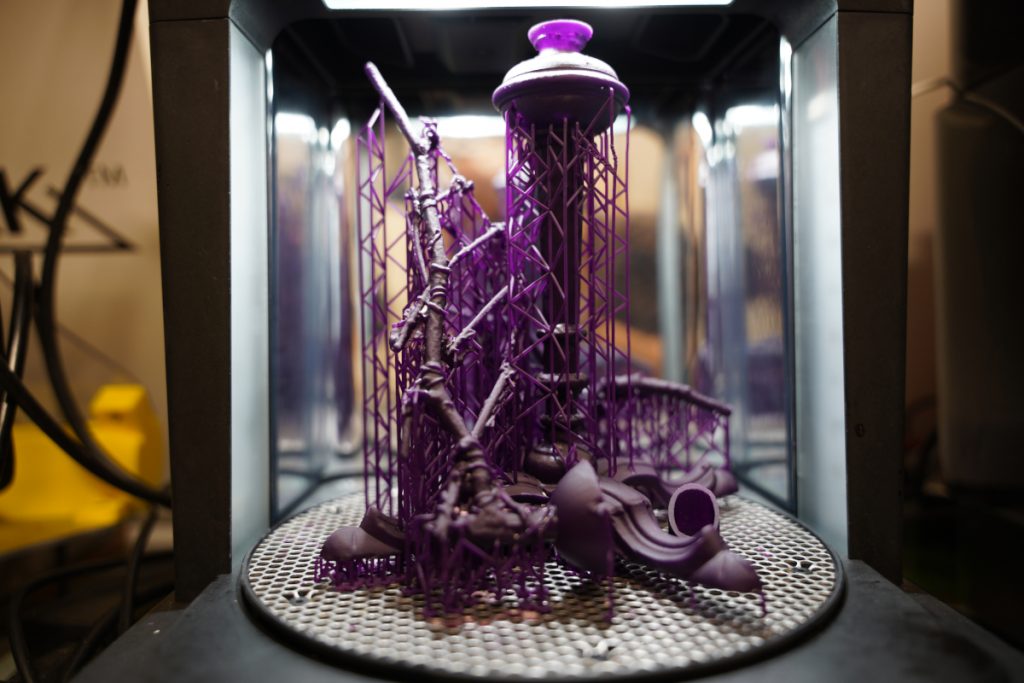

The method of assemblage, which I use to create models of my sculptures, is much more complex than just gluing things together. I collect different objects and textures to have a kind of “library.” Then I choose the ones I like, make plaster moulds, and fill them with wax. Thus, I get the elements which I can freely multiply, modify, and join. It is a very enjoyable and creative stage. Recently, I have discovered that I can assemble models of my sculptures in virtual space, and this method gives me even more freedom. I scan different elements in 3D, then model them with the use of 3D programs, and finally, print them.

Regardless of what material the sculpture model is made, most of them are finally cast in metal: bronze, aluminium, or iron. I always mould and cast my works myself. Although I have not studied metal casting as a science, it has been an integral part of my creative practice for 17 years. In the era of simple and fast solutions, this traditional and demanding method seems to be quite a challenge for an artist. For me, the whole process becomes a ritual, a journey in which I have a chance to stay in touch with my sculpture and the material on every stage of its creation. In this process I find peace and stability.

I have built four outdoor furnaces for melting iron at the Academy of Art and Design in Wrocław, where I work. Three of them are the cupola type, and one is a tilting furnace. I cooperate with other iron casters from around the world—both artists and scientists. It is important for me to use different moulding materials and techniques, because the knowledge of their pros and cons allows me to choose the optimal ones for the particular project. The processes I use range from those ancient ones in which natural materials like horse manure, clay, and charcoal are used, to those most contemporary ones, used in industry (e.g., sodium silicate or ceramic shell moulds).

I organize workshops and iron pours in order to share my knowledge and experience with students and other artists. Sharing was also one of the main ideas behind the Festival of High Temperatures, which has been organized at the Academy since 2007. I was a co-founder and have been an organizer of the event. The festival combines art and science, the participants are not only professional artists but also people interested in art and science.

To see Staszczak present his centrifugal casting process, you can watch this video.

Artwork/Exhibition you are most proud of:

I am most proud of my recent exhibition titled Size Matters, which took place in the Wałbrzych Gallery of Art. I showed sculptures from the Pain Forest series which consists of works created in the years 2016-2021. The works are surreal assemblages composed of the elements derived mainly from nature—horns, seeds, bones, tentacles, sticks, etc. The creatures that emerge from my art do not exist in reality, but I try to “deceive” the viewer otherwise. The natural realm really fascinates me, but I transform it through my imagination. The series is called Pain Forest because I want to refer to the suffering of nature caused by people and civilization.

A lot of works presented at the exhibition were created in 3D technology, which offers an additional, fascinating possibility—the same work can be made in different sizes. With a few clicks, I can decide whether it will be a large spatial object or a filigree, almost jewelry sculpture. By juxtaposing the same sculpture in different sizes, I want to initiate an interaction between its different “versions” and show that size really matters. Depending on the size, the objects evoke various emotions and associations; other details attract attention.

Other questions also arise. Is it the same sculpture? Which one is a copy and which is the original? Or maybe the original is the STL or OBJ file from which they were printed? Does their multiplication diminish their originality? Or maybe in the reality of the mass production that surrounds us, their uniqueness lies in the original idea of the artist who created them?

Certainly, the possibility of relatively easy scaling of the object gives the sculptor an additional tool to be used in the creative process, and the use of 3D technology in the process of creating sculptural objects allows artists to combine tradition with the latest technological achievements. However, in many cases, the decision to choose the “best and appropriate” size for a given object is impossible.

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

There are a lot of artists I look up to, and most of them create cast metal art. I have had a chance to participate in a few international cast iron art events, and they were a great opportunity to meet a lot of wonderful artists and see their sculptures in person. I have also hosted a lot of artists at the Academy of Art and Design in Wrocław.

I think my most honourable guest was Wayne E. Potratz, a great sculptor and professor emeritus of the University of Minnesota. Professor Potratz is an undeniable authority in the field of cast metal art, with amazing experience and knowledge. During his stay in Wrocław, he led a workshop of making recyclable moulds with natural materials. This ancient method is very simple and effective. Another amazing artist I had a chance to work with was Andy Griffiths. He created a lot of site-specific works and was famous for his unforgettable performances with cast iron. What these two artists have in common is their passion to share knowledge with others. They have certainly been a great inspiration for many people.

SciArt is an emerging term related to combining art and science. How would you define it?

Science is a very broad term, and I think it has always been used by artists who needed it to be able to use “traditional” materials or technologies in the creative process. Nowadays, there are no limits for artists. Not only can they experiment with very advanced materials and technologies, but also make science the main subject of their work. They can either learn whatever they need from a variety of sources, or they can easily find professional support and start collaborations with scientists in any field. On the other hand, scientists also appreciate working with artists because they can gain a new perspective on their research; they are inspired by artists’ creative flow and sometimes are forced to find completely new solutions to enable the realization of even the strangest artistic vision.

For more by Michał Staszczak, visit his website, Instagram, and Facebook.

*

Featured image: Tadpole, Maxi (2021) and Tadpole, Midi (2021) by Michał Staszczak, 33 x 31.5 x 90.5 in, & 12.5 x 11 x 29 in, PLA.

All images courtesy of the artist.

Share this Post